NONCOMMITTAL for KINDLE or LESS THAN KIND?

One must of course strive to remain open-minded. Most often – and most persuasively – attributed to Sir Thomas Beecham is the remark: “One should try everything once, except incest and Morris dancing”. On the other hand, advancing years dull the appetite for novelty. I see no prospect that in the time left to me I shall ever attend a baseball match, visit either pole, take up crochet, read a Jeffrey Archer novel, bungee-jump, join the SAS, restore a classic car, learn the trombone, watch Britain’s Got Talent, make love to Zsa Zsa Gabor or run a half-marathon. Over none of these do I lose sleep.

But technology is apt to bring the unthinkable within reach. For years, I owned a word processor without ever being curious about its parallel functions as a computer. It did what I needed it for and the rest was just another displacement activity. Since switching to Mac in the 1990s, a whole other world has opened up.

There will be those, I do not doubt, who will tell me that a comparable world will burst before me like a flower if I invest in a Kindle. Yet I find myself no more drawn to this device than to watching Nip/Tuck or holidaying on Ibiza. Is this a prejudice on my part or is it a realistic assessment of how the device will surely fail to dovetail with my habits, needs and inclinations?

A book

I have never handled a Kindle nor seen one in the flesh. I believe I grasp what it does, but my knowledge may be imperfect. Correct me if I am wrong but here goes: it is a form of digital tablet dedicated to downloading, storing and displaying print, primarily in the form of pre-existing books, periodicals, newspapers and other publications. Hence it also goes by the designation of an ebook reader, which is to say a personal computer for reading purposes.

The very idea makes my head ache. It may not be as barbaric as watching a movie on your mobile phone – the notion of sitting through a four-inch-by-two-inch screening of Abel Gance’s Napoléon beggars belief – but when I perforce spend so many of my waking hours training my declining eyesight on various kinds of screen, I need a different kind of texture to rest my eyes upon for reading, and indeed one that is in light rather than emitting light.

But look, the Kindlean will explain, you can pack an effective infinity of books for a trip without breaching luggage restrictions. That may well be so. But I am a slow reader. A substantial novel – a Dickens, a Lawrence Norfolk, even a John Irving – will generally see me through the sojourn and back, and I can always pick up something if I should finish unwontedly soon. What’s more, I’m not at all sure I could handle an infinity of choice. One might find oneself sliding into the unacceptable custom of not finishing a book. Let me make my bargain with a single volume and keep my end of it, trusting that the writer will have kept hers.

This infinity thing is definitive for me. I don’t want a multitude of possibilities. I want to have chosen already. I have been acquiring books since childhood and I have shed hardly any volumes along the way – for instance, I still possess pretty much all of Beatrix Potter and a smattering of Enid Blyton.

A Kindle thingy

From my maternal grandfather, already a schoolmaster when Victoria reigned, I have a set of various novels, illustrated and identically board-bound, that includes Jane Eyre, Westward Ho! and David Copperfield but also such lost masterpieces as Charles Lever’s Harry Lorrequer and John Halifax, Gentleman by Mrs Craik. I was going to make a smart point about books like that not being available as ebooks, but a moment’s on-line research has confounded me.

The wider point, though, is that I already have a library. Jonathan Franzen, who is twelve years younger than me, remarked some years ago that he had totted up his book collection, calculated his life expectancy and his rate of book consumption, and discovered that he had more books than he could possibly read. That must have been true of me half a lifetime ago, but I have felt no compunction in adding to the store. A large part of the pleasure of books is the having of them. This is a pleasure unknown to Kindle.

Perhaps possession is not quite nine-tenths of the love but it means a lot. If you can just snag anything you fancy on Kindle, where’s the fun? There’s no substitute for trawling through second-hand bookstores and stumbling on unimagined treasures. What proper book-lover has ever left an antiquarian bookshop empty-handed? And then there’s the joy of entering an unfamiliar bookseller’s and happening upon that edition, tucked at the end of a shelf, that you have sought for years. What does Kindle know of “editions’?

It’s the nebulous nature of the on-tap character of the material that repulses me. It’s why I was never able to get into Spotify. I love downloading music. It’s on my iMac, I can go through my comprehensively organised lists and decide what to play, knowing pretty much what the choice encompasses. But with Spotify, the “jukebox in the sky”, it will take me half the evening to narrow down my choice and then if I happen to catch something I like but don’t know, will I be able to find it again? Do I want that much shuffling to do with stuff I don’t actually own?

Bookshelves: lead me to 'em

This supposed cornucopia of availability robs the book-lover of all the pleasure of the search and the chase, the voyage specifically to track down a new or old volume, the delight of having it between your hands for the first time, of smelling its essence, of squeezing the texture and thickness of its paper between your fingers, of appreciating (or perhaps not) the publisher’s choice of cover, of font, of dimensions, of physicality.

Books are a physical pleasure. Handling them is as sensual as anything this side of sex. I love to linger by our shelves, looking at spines, pulling out odd volumes, noting which have still to be read. I love to see the progress of my reading a book described in the creases on the spine. Some book-lovers abhor such treatment, considering it sacrilege. In my turn, I deprecate turning down the corners of pages. Bookmarks are delightful objects and I collect small leather ones wherever I go, purely for sliding in between the pages where I last stopped reading. Kindle has no such supplementary delights. Oh yes, I’m sure you can have the functions, just not the sweetness.

But in this age of interactivity, you will increasingly be able to add to the ebook. I don’t much care for the annotations of others and am put off buying an old tome if I spot marginalia and other emendations. The passing of years does not generally render the passing remarks of others less banal. Now, apparently, you can “highlight” passages of books on Kindle and, when a certain number of readers have marked the same passage, it will be flagged for your attention as you read. How crass.

This is all of a piece with the “clips” culture that rules on television, so that every past programme is known for a celebrated moment. I am so glad that I saw the first transmission of those episodes of Only Fools and Horses in which Del-boy fell through the bar and the chandelier fell from the ceiling. The delight – unimaginable now – is that one didn’t know that these things were going to happen.

Anne Fadiman: irresistible

There’s a parallel convention in newspapers where what is called a “pull-quote” is drawn from a piece and printed large in the margin or where an illustration might have gone. Often this quote will be the article’s best joke, thereby ruined by being blown up out of context. Equally often, the quote will be slightly rewritten for length so that it is not even an accurate quote. It’s not an aspect of journalism that I miss, now that I am out of that game.

All of this speaks to the urge to “promote” a book in particular, writing in general. There is a certain amount of cover promotion on books that I try to avoid. If I find a sticker on a book, shouting that it has been read on Radio 4 or has won the Orange Prize, I will ascertain that the sticker is peelable before I purchase. One of Patrick Gale’s novels will not join my shelves until the publisher brings out an edition that does not carry a quote from the allegedly omniscient Stephen Fry on the cover. These things matter with books. They do not enter the equation with Kindle because the whole transaction is so impersonal.

Indeed, there are myriad concerns over the possession of books, of all of which the ebook reader is innocent. There is the matter of inscriptions, some of them remarkably historic and/or plangent. Here is a pertinent observation from a book dealer in Chipping Campden: “Imagine how delightful it would be to own an edition of Thomson’s The Seasons with this authenticated inscription: To my dear friend John Keats in admiration and gratitude from PB Shelley, Florence 1820. Imagine, too, how depressing to have an otherwise fine first of Milton’s Paradise Lost with this ball-point inscription scrawled on the title page: To Ada from Jess, with lots of love and candy floss, in memory of a happy holiday at Blackpool, 1968”.

This quote derives from Ex Libris. Its author, the American bibliophile Anne Fadiman, counts among her other topics the housing of books and what she calls “my odd shelf”. No one may seriously reckon to be a book-lover while neglecting to read Anne Fadiman. Her joy in books is a joy twice over.

But that is the nub of it. If you love books qua books, you could never hug a Kindle to your bosom. Don’t talk to me about how practical it is. Who cares? Love is not practical. Love is a fine madness. If every book ever published can be got through Kindle, why would you feel the compulsion to read any of them? I obsessively tend the tottering pile of books by my bed, barely able to forbear from breaking into the top one before the current one is exhausted. Periodically I change my opinion about which I will read next-but-two-or-three, or I slip another into the pile. I never remove one that has been promoted to this eminence of imminence. You may call this semi-psychotic behaviour. I think proper book-lovers will recognise similar traits in their own passionate attachment to the physical presence rather than the digital abstraction of reading.

Saturday, March 31, 2012

Labels:

Anne Fadiman,

books,

bookshops,

computers,

iMac,

Jonathan Franzen,

Kindle,

Only Fools and Horses,

Spotify

Tuesday, March 20, 2012

STRAIGHT to the HEART

Gay marriage: oh dear, oh lor’, how did this become the issue of the hour? The world appears to have divided itself into two camps and I find myself in neither. Nor do I truly understand either. One strikes me as vindictive, proscriptive, oppressive and presumptuous, the other wrong-headed, unrealistic, provocative and equally presumptuous. Leave me out, please.

Here’s what I bring to the table. I was raised an only child in a household that paid unexamined lip service to the Church of England but never set foot in a church except on high days and holidays. For a brief time ahead of adolescence, I became fervently religious, joined the Bible Reading Fellowship and read a passage of scripture every day before going to sleep. Within a very few weeks of my confirmation, it dawned on me that the whole of religion was supernatural superstition and a dangerous and wicked confidence trick, eagerly taken up by the ruling class as a means of keeping the masses in their place on the promise of jam tomorrow. My take on it has not fundamentally altered since then, though I hope I now express it in more sophisticated terms.

Long before my five minutes of mystical romanticism, I knew that I looked at boys in a significantly different way from how I looked at girls. But there was no roadmap for finding one’s way across this treacherous terrain. To be “queer” – then strictly a term of abuse – was to be an outlaw and an outcast. Those public figures who were widely understood to be “queers” – Godfrey Winn, Beverley Nichols, Somerset Maugham, John Gielgud – shared a certain demeanour that was apt to repel a small boy who wanted to be accepted and approved.

Nichols, Winn, Maugham, Gielgud

Like most of my gay contemporaries, I tried to be straight because I didn’t want to go to jail or be spurned by my family and friends or be unable to get a job or be obliged to live in a twilight world (whatever one of those was). I certainly didn’t want to make my mark on the culture by being interviewed in silhouette on television, sounding defeated and desperate.

I was twenty years old before the law was changed and sexual acts between men were permitted in certain relatively limited situations. By then I was well used to being and feeling an outlaw and this context for my sexuality doubtless coloured my attitudes to everything else in my life.

A change in law does not immediately change society and it took time for me fully to reconcile myself to what and who I was and to feel confident and self-possessed enough to reveal that to others. Relationships with men who embraced their freedom more instinctively than I could, along with the gradual dawning of the gay liberation movement, swept me along. Within seven or eight years of the law changing, I was beginning to feel able to present myself as “a gay man” – still a relatively new phrase – though the instinct to cling to a safety net of being “really” bisexual still lingered.

Once I was “out” – another new and bracing notion – as a journalist addressing a public readership, there was no going back. And perhaps the sensation of burning bridges was the most liberating ingredient of all. In the heady days of the Gay Liberation Front and the first Gay Pride marches – I can still picture the face of the skinhead denouncing us from the pavement and my chum Richard demanding “did you see what just called me ‘scum’?” – we began to discuss every aspect of what it meant to be a gay man; we knew from the outset that we didn’t dare speak for lesbians, especially the ferocious sisters who designated themselves “lesbian separatists”.

And on one thing we were very clear. We didn’t want marriage. It was an article of faith that we had no intention of aping the straight world, its requirements and conventions, its rituals and charades. We were forging new ways of conducting relationships, so we were never going to model ourselves on how our parents negotiated their respective territory. Our relationships – if indeed we even tolerated anything remotely resembling “a relationship” – were going to be open and permissive and equal and progressive. And we certainly weren’t about to pay any attention to what we were told to do by notionally monogamous vicars and their Catholic equivalents who were expected to be virgins.

The original GLF badge

The painfully slow embrace of each other by the gay community and the larger society has evidently required and has indeed achieved adjustments on both sides. David Cameron’s famous line at conference last year – “I don’t support gay marriage in spite of being a Conservative. I support gay marriage because I am a Conservative” – was widely seen as an impeccably liberal, enlightened stance.

I’m not so sure. I think the key word for Cameron in that sentence is not “gay” but “marriage”. And it revives my own instincts of forty years ago to maintain a healthy mistrust of straight society’s wish to bring us into the fold, draw our teeth and turn us into well-behaved little conservatives, big C and small. With Groucho Marx, “I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member”.

In the present dispensation, the Cameron Tories are in advance of the thinking of the church hierarchies, but perhaps only because they live more in the real world. After all, the Tory Party, the Anglican Church and the Catholic Church would all grind to a halt if their gay members left en masse, whatever the official line might be.

All three institutions have their share of unreconstructed reactionaries who think that they make an unanswerable case by loudly proclaiming that marriage between a man and a woman is “natural” and any other kind of union is not. Of course, marriage is merely an ancient social convention, with no equivalent among any other natural orders of living creatures. Some fauna mate for life, most don’t, and some – whisper it – go in for same-sex action.

A GLF publication

Nature is hardly a reliable guide for anything much at all. The “natural” brigade do not stop to think that it is wholly unnatural for humans to fly, yet most of them do it routinely and have done so for a century. And what is natural about playing golf, watching the telly, getting drunk, riding to hounds, sending emails, counting one’s money, learning the cello, mounting a picket line or indeed getting down on one’s knees and parroting responses when a man in a dog collar asks his flock to do so? What to you is not “natural” –- by which you mean acceptable – is second nature to me.

Those who hold the institution of marriage in something approaching reverence conveniently ignore how it may be used as a weapon of oppression against those weakened by it – battered wives, for instance, or abused children – or how it may provide a smokescreen behind which all manner of shenanigans may obtain, not least the sham or convenience marriage. Moreover, marriage is not in itself any guarantee of a lasting union, even when entered into in good faith. Monarchists prate self-importantly about the example and stability of the royal family as if it were not rather more dysfunctional than the general run of commoner families, three of Her Majesty’s four children having been through divorce.

But then those of us who spurn marriage might think it, with Hamlet, “a custom/More honoured in the breach than the observance”. Herein lies my suspicion of those lesbians and gay men who demand the right to marriage. I no more want to join a club that until very recently didn’t want me as a member than I do a club that now says I am welcome.

If it’s the supposed security of being formally recognised as half of a couple that is desired, well, I find that civil partnership fulfils such a function admirably. It gives the partner pretty much the same legal, social and financial rights that a spouse enjoys. My own partner and I could see the advantages of signing up for this piece of societal recognition and did so in the first months of its availability. But we won’t be getting married.

Scotland's first civil partnership ceremony

Why indeed do any LGBT people wish to have a wedding, whether civil or religious? Maybe for some it is the excuse for a party or, more specifically, a celebration, but you could have that without any formal proceedings. Pace David Furnish and Elton John, our civil partnership ceremony was the quietest and most private we were permitted: just two statutory witnesses and no “wedding breakfast”. We told no one else until afterwards. Of course the downside was that there were hardly any presents, but old crocks like us are hard to buy for at the best of times.

For those who indulge in mumbo-jumbo, trying to get organised orders of superstition to throw away the preferred readings of age-old texts is bound to cause trouble, if not schism. The Church of England has been tottering for years now, poised to split on the issue of gay rights. The appointment of Rowan Williams’ successor as Archbishop of Canterbury will be more minutely examined for what it tells us about the church’s future attitude to gay marriage than for any other signs.

Not my problem, but I think my fellow gays should favour society’s recognition of their sexuality over any concessions grudgingly clawed from Synod. After all, it makes little sense to subscribe voluntarily to an enterprise that has plenty of ancient regulations set down and widely known, and then decide that you can’t “be yourself” if you don’t get the regulations changed. For that walking contradiction “the gay Christian”, it is the Christianity, not the being gay, that is the problem.

So I cannot find in my heart any empathy for those who want to eat their cake and have it too, who want to be accepted and free in their sexuality in a community that is fundamentally homophobic, right down to its written constitution.

Of course, same-sex relationships are no easier than any other kind

But if those who yearn to be embraced by their enemy are the uneatable (in Wilde’s formulation), those who hound them are the unspeakable. I feel a particular enmity towards one of the ringleaders of the backbench backwoodsmen whose notion of a debating point is characteristically to direct such ad hominem observations as “claptrap” against those who advocate and support marriage for gay people. He is an ugly piece of work called Peter Bone. Heterosexual men like to affect that their deepest fear is that gay men will try to molest them, but I can reassure Mr Bone that he raises no boner in the gay community.

Since 2005, Mr Bonehead – oh tsk, tsk, I must guard against joining him in the gutter of personal abuse – has been the MP for Wellingborough, the Northamptonshire town in which I grew up. I also enjoyed my inaugural sexual experiences in the constituency that Mr Bone now represents so diligently. If you wonder whether those experiences were homosexual or heterosexual, I give you Gore Vidal’s answer: “I was too polite to ask”.

P Bone telling the Commons that the coalition's determination to allow same-sex marriage is "completely nuts"

Wellingborough is not quite the first place to which I would direct anyone seeking enlightenment, especially in the sphere of sexuality. It is not a community comparable to Amsterdam or San Francisco, Berlin or even Brighton. On a sign announcing the town’s imminence on one’s route, a local wag has obliterated five of the middle letters of its name so that it reads “Well ….. rough”. It’s not a wholly unearned notion.

When I was no’but a lad (as people are more apt to say well to the north of Northants), Wellingborough was a quiet, modest town of some 25,000 souls, supporting a cattle market, five cinemas, a tiny zoo, a range of individual enterprises and a thriving boot and shoe industry. All that has changed. In the 1960s, the place was chosen as a major overspill town to accommodate people transferred from London and, in the coming decades, a further expansion will push the population well over 60,000. Perhaps the newcomers will prove more liberal in their attitudes than Peter Bone can imagine. For aught I know, there may even be actual queers living in the constituency right now.

Gay marriage: oh dear, oh lor’, how did this become the issue of the hour? The world appears to have divided itself into two camps and I find myself in neither. Nor do I truly understand either. One strikes me as vindictive, proscriptive, oppressive and presumptuous, the other wrong-headed, unrealistic, provocative and equally presumptuous. Leave me out, please.

Here’s what I bring to the table. I was raised an only child in a household that paid unexamined lip service to the Church of England but never set foot in a church except on high days and holidays. For a brief time ahead of adolescence, I became fervently religious, joined the Bible Reading Fellowship and read a passage of scripture every day before going to sleep. Within a very few weeks of my confirmation, it dawned on me that the whole of religion was supernatural superstition and a dangerous and wicked confidence trick, eagerly taken up by the ruling class as a means of keeping the masses in their place on the promise of jam tomorrow. My take on it has not fundamentally altered since then, though I hope I now express it in more sophisticated terms.

Long before my five minutes of mystical romanticism, I knew that I looked at boys in a significantly different way from how I looked at girls. But there was no roadmap for finding one’s way across this treacherous terrain. To be “queer” – then strictly a term of abuse – was to be an outlaw and an outcast. Those public figures who were widely understood to be “queers” – Godfrey Winn, Beverley Nichols, Somerset Maugham, John Gielgud – shared a certain demeanour that was apt to repel a small boy who wanted to be accepted and approved.

Nichols, Winn, Maugham, Gielgud

Like most of my gay contemporaries, I tried to be straight because I didn’t want to go to jail or be spurned by my family and friends or be unable to get a job or be obliged to live in a twilight world (whatever one of those was). I certainly didn’t want to make my mark on the culture by being interviewed in silhouette on television, sounding defeated and desperate.

I was twenty years old before the law was changed and sexual acts between men were permitted in certain relatively limited situations. By then I was well used to being and feeling an outlaw and this context for my sexuality doubtless coloured my attitudes to everything else in my life.

A change in law does not immediately change society and it took time for me fully to reconcile myself to what and who I was and to feel confident and self-possessed enough to reveal that to others. Relationships with men who embraced their freedom more instinctively than I could, along with the gradual dawning of the gay liberation movement, swept me along. Within seven or eight years of the law changing, I was beginning to feel able to present myself as “a gay man” – still a relatively new phrase – though the instinct to cling to a safety net of being “really” bisexual still lingered.

Once I was “out” – another new and bracing notion – as a journalist addressing a public readership, there was no going back. And perhaps the sensation of burning bridges was the most liberating ingredient of all. In the heady days of the Gay Liberation Front and the first Gay Pride marches – I can still picture the face of the skinhead denouncing us from the pavement and my chum Richard demanding “did you see what just called me ‘scum’?” – we began to discuss every aspect of what it meant to be a gay man; we knew from the outset that we didn’t dare speak for lesbians, especially the ferocious sisters who designated themselves “lesbian separatists”.

And on one thing we were very clear. We didn’t want marriage. It was an article of faith that we had no intention of aping the straight world, its requirements and conventions, its rituals and charades. We were forging new ways of conducting relationships, so we were never going to model ourselves on how our parents negotiated their respective territory. Our relationships – if indeed we even tolerated anything remotely resembling “a relationship” – were going to be open and permissive and equal and progressive. And we certainly weren’t about to pay any attention to what we were told to do by notionally monogamous vicars and their Catholic equivalents who were expected to be virgins.

The original GLF badge

The painfully slow embrace of each other by the gay community and the larger society has evidently required and has indeed achieved adjustments on both sides. David Cameron’s famous line at conference last year – “I don’t support gay marriage in spite of being a Conservative. I support gay marriage because I am a Conservative” – was widely seen as an impeccably liberal, enlightened stance.

I’m not so sure. I think the key word for Cameron in that sentence is not “gay” but “marriage”. And it revives my own instincts of forty years ago to maintain a healthy mistrust of straight society’s wish to bring us into the fold, draw our teeth and turn us into well-behaved little conservatives, big C and small. With Groucho Marx, “I don’t care to belong to any club that will have me as a member”.

In the present dispensation, the Cameron Tories are in advance of the thinking of the church hierarchies, but perhaps only because they live more in the real world. After all, the Tory Party, the Anglican Church and the Catholic Church would all grind to a halt if their gay members left en masse, whatever the official line might be.

All three institutions have their share of unreconstructed reactionaries who think that they make an unanswerable case by loudly proclaiming that marriage between a man and a woman is “natural” and any other kind of union is not. Of course, marriage is merely an ancient social convention, with no equivalent among any other natural orders of living creatures. Some fauna mate for life, most don’t, and some – whisper it – go in for same-sex action.

A GLF publication

Nature is hardly a reliable guide for anything much at all. The “natural” brigade do not stop to think that it is wholly unnatural for humans to fly, yet most of them do it routinely and have done so for a century. And what is natural about playing golf, watching the telly, getting drunk, riding to hounds, sending emails, counting one’s money, learning the cello, mounting a picket line or indeed getting down on one’s knees and parroting responses when a man in a dog collar asks his flock to do so? What to you is not “natural” –- by which you mean acceptable – is second nature to me.

Those who hold the institution of marriage in something approaching reverence conveniently ignore how it may be used as a weapon of oppression against those weakened by it – battered wives, for instance, or abused children – or how it may provide a smokescreen behind which all manner of shenanigans may obtain, not least the sham or convenience marriage. Moreover, marriage is not in itself any guarantee of a lasting union, even when entered into in good faith. Monarchists prate self-importantly about the example and stability of the royal family as if it were not rather more dysfunctional than the general run of commoner families, three of Her Majesty’s four children having been through divorce.

But then those of us who spurn marriage might think it, with Hamlet, “a custom/More honoured in the breach than the observance”. Herein lies my suspicion of those lesbians and gay men who demand the right to marriage. I no more want to join a club that until very recently didn’t want me as a member than I do a club that now says I am welcome.

If it’s the supposed security of being formally recognised as half of a couple that is desired, well, I find that civil partnership fulfils such a function admirably. It gives the partner pretty much the same legal, social and financial rights that a spouse enjoys. My own partner and I could see the advantages of signing up for this piece of societal recognition and did so in the first months of its availability. But we won’t be getting married.

Scotland's first civil partnership ceremony

Why indeed do any LGBT people wish to have a wedding, whether civil or religious? Maybe for some it is the excuse for a party or, more specifically, a celebration, but you could have that without any formal proceedings. Pace David Furnish and Elton John, our civil partnership ceremony was the quietest and most private we were permitted: just two statutory witnesses and no “wedding breakfast”. We told no one else until afterwards. Of course the downside was that there were hardly any presents, but old crocks like us are hard to buy for at the best of times.

For those who indulge in mumbo-jumbo, trying to get organised orders of superstition to throw away the preferred readings of age-old texts is bound to cause trouble, if not schism. The Church of England has been tottering for years now, poised to split on the issue of gay rights. The appointment of Rowan Williams’ successor as Archbishop of Canterbury will be more minutely examined for what it tells us about the church’s future attitude to gay marriage than for any other signs.

Not my problem, but I think my fellow gays should favour society’s recognition of their sexuality over any concessions grudgingly clawed from Synod. After all, it makes little sense to subscribe voluntarily to an enterprise that has plenty of ancient regulations set down and widely known, and then decide that you can’t “be yourself” if you don’t get the regulations changed. For that walking contradiction “the gay Christian”, it is the Christianity, not the being gay, that is the problem.

So I cannot find in my heart any empathy for those who want to eat their cake and have it too, who want to be accepted and free in their sexuality in a community that is fundamentally homophobic, right down to its written constitution.

Of course, same-sex relationships are no easier than any other kind

But if those who yearn to be embraced by their enemy are the uneatable (in Wilde’s formulation), those who hound them are the unspeakable. I feel a particular enmity towards one of the ringleaders of the backbench backwoodsmen whose notion of a debating point is characteristically to direct such ad hominem observations as “claptrap” against those who advocate and support marriage for gay people. He is an ugly piece of work called Peter Bone. Heterosexual men like to affect that their deepest fear is that gay men will try to molest them, but I can reassure Mr Bone that he raises no boner in the gay community.

Since 2005, Mr Bonehead – oh tsk, tsk, I must guard against joining him in the gutter of personal abuse – has been the MP for Wellingborough, the Northamptonshire town in which I grew up. I also enjoyed my inaugural sexual experiences in the constituency that Mr Bone now represents so diligently. If you wonder whether those experiences were homosexual or heterosexual, I give you Gore Vidal’s answer: “I was too polite to ask”.

P Bone telling the Commons that the coalition's determination to allow same-sex marriage is "completely nuts"

Wellingborough is not quite the first place to which I would direct anyone seeking enlightenment, especially in the sphere of sexuality. It is not a community comparable to Amsterdam or San Francisco, Berlin or even Brighton. On a sign announcing the town’s imminence on one’s route, a local wag has obliterated five of the middle letters of its name so that it reads “Well ….. rough”. It’s not a wholly unearned notion.

When I was no’but a lad (as people are more apt to say well to the north of Northants), Wellingborough was a quiet, modest town of some 25,000 souls, supporting a cattle market, five cinemas, a tiny zoo, a range of individual enterprises and a thriving boot and shoe industry. All that has changed. In the 1960s, the place was chosen as a major overspill town to accommodate people transferred from London and, in the coming decades, a further expansion will push the population well over 60,000. Perhaps the newcomers will prove more liberal in their attitudes than Peter Bone can imagine. For aught I know, there may even be actual queers living in the constituency right now.

Monday, March 12, 2012

The ELEPHANT is STILL in the ROOM

Yes, of course the best political entertainment this year has been the tussle for the nomination to represent the Republican Party in November’s US presidential election. Democrat Party supporters, the chattering classes and enlightened, informed people everywhere have pointed and laughed to scorn, while Barack Obama – no slouch he – has quietly got on with amassing the most gigantic electoral war-chest in global history and turning every public appearance into a stump speech.

The Republicans have no one to blame but themselves if they appear to be careering to defeat. Since the 2008 election, they have allowed the Tea Party and its bankrollers to annexe the GOP agenda and to muscle in on its choice of candidates. Both in their general demeanour and in the kind of candidate behind whom they have lined up, Tea Partiers have been blithely unafraid of looking like the lunatic fringe. Unhappily for them, this has paid diminishing returns as the months roll inexorably towards judgment day.

The Republican elephant – or possibly a mammoth

Candidates with uncompromising, irrational views tend to look wilder and flakier the more they are exposed to public scrutiny. And the unblinking attention of the media, even when it is that of Fox News, is merciless in cutting these numbskulls down to size. The Sarah Palin phenomenon seems to have burned out at last. Her successors as the darlings of the right – Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Herman Cain – quickly proved utterly inadequate to the task. Those still standing – Mitt Romney, Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul – have failed to gather irresistible momentum beyond their respective (and very distinct) core support.

Romney is the establishment choice, precisely because he isn’t a product of the Tea Party bubble. Like his father, George W Romney, he was a liberal Republican governor of a northern state (though Mitt stood down after one term) and, eerily repeating history, the son is also the front-runner in a race for the candidature but prone to hobbling his own case, just like the father. In 1968, George W allowed himself to be decisively overtaken by Richard Nixon. Unlike his father, Mitt has built ruthlessly on inherited wealth – George W was a self-made man -– and his financial ethics have been talked up as a potent liability by his Republican rivals, most usefully for the Democrats’ electoral machine. Mitt’s own uncanny knack for sounding the wrong kind of sang froid about his wealth and thus making his business success seem even more of a millstone may yet deny him the party nomination in August. A lot can happen in five months.

The Democrats' donkey (now retired)

It’s a curiosity of American iconography that the major political parties’ emblems are arse about face. The Grand Old Party presents itself as an elephant but its ability to forget – to rewrite history and move rapidly on – is unrivalled. The Democratic Party has dropped the donkey as its emblem, perhaps finally aware that it was ever incapable of delivering the donkey’s proverbial backwards kick. Since World War II, both parties have run with candidates who stood no chance – George McGovern (still around, rising 90) and Fritz Mondale for the Democrats, Barry Goldwater and Bob Dole for the Republicans – but the ferocity with which the doomed candidate’s party rivals slug it out cannot be compared. For instance, the story of George W Romney’s opposition to the candidacy of the right-wing fundamentalist Goldwater in 1964 is worth seeking out. Mitt lacks Dad’s killer instinct.

Not so great after all: the other George W

When it comes to the crunch, the Republican Party – like Britain’s Tories – is most always mindful of its own best interests and ruthless in the despatch with which it divests itself of a candidate it knows cannot win. Don’t discount the possibility of someone not now running being drafted to rescue the cause. In this campaign, the GOP has faced an unprecedented dilemma because the immeasurable power of the Tea Party makes everything so uncertain. The invisible Koch Brothers, without whose billions the Tea Party would be nothing, exert huge power but lack the practical political skills to see what both the immediate and the long-term effects of that power might be. And the Washington elite has not had to deal with such incoming power before. There is no roadmap for what is going down.

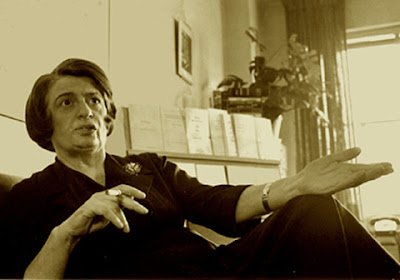

In a provocative assessment, widely circulated, George Monbiot credits the eccentric Russian émigrée writer Ayn Rand (who died thirty years ago this month) as the source of much current right-wing philosophy in the US. I do not doubt for a moment that Rand has had her adherents – many of them, intriguingly, in Silicon Valley – but Monbiot quotes a Zogby survey (which I cannot locate on the internet) to the effect that one American in three has read Rand’s notorious philosophical treatise, Atlas Shrugged. I apologise – disputing with George Monbiot is not to be undertaken lightly – but one-third of the US has certainly not heard of Rand, let alone read her. I should be more persuaded by a finding that one in three Americans has not read a book of any kind since leaving high school.

Atlas Puffed: Ayn Rand

Rand was undeniably influential – let’s not forget that Alan Greenspan, who ran the Federal Reserve for twenty years, was a close protégé – but in terms of public recognition she was no Oprah Winfrey. She constructed her own slant on the American dream but she did not originate or even embody the articulation of that dream. James Truslow Adams’ 1931 treatise Epic of America attempts a summary that still serves: “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement … It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable and be recognised by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position”.

The peculiar contribution Rand made to the dream was to argue that opportunity and attainment are constrained by regulation and concern for others, that the American dreamer should shrug off the pettifogging attentions of authority and government and the finer feelings of his neighbours and ruthlessly pursue the dream. It was a more incisive spin on a staple, age-old figure from American myth and literature, offered again and again to the public especially through the medium of cinema: the romantic individualist, the maverick, the heroic outlaw, the lawman who breaks all the rules, the righteous man of action.

Mitt marries his Ann, 1969

Truslow Adams perceived that the American dream was inherently a repudiation of European class and caste, hierarchy and inheritance. In the American dream, all might rise – in the pre-feminist legend, any boy could grow up to be President – and birth, school, club and all such masonic connections would count for nothing. Rand took this further, preaching that community and social interdependence also counted for nothing. There is a clear echo in Margaret Thatcher’s famous retort during a 1987 interview for Woman’s Own: “[people] are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour”.

Santorum: "Some gay men are this big"

Barack Obama has been widely “accused” of being a Socialist – not, of course, by Europeans who know what a Socialist is, but by Americans. That is because Obama has made a few small gestures towards trying to relieve the plight of the poor and the unemployed and those who cannot afford health cover. Even with the prevailing philosophy of the post-Blairite governing class in Britain, wherein more and more social provision is either outsourced to racketeers or withdrawn altogether, Obama’s achievements look small beer. By a rich piece of irony, Mitt Romney introduced health care measures in Massachusetts during his governorship that in many ways provided the model for Obama’s federal health care reform of 2010. Romney is no more a Randian by nature than is Obama.

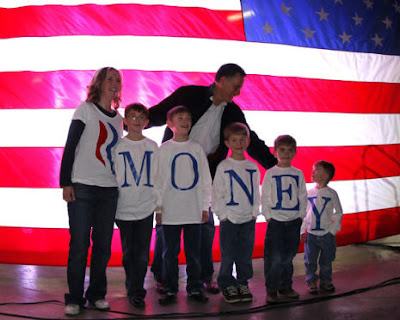

The letters of 'Mint' Romney's name come sadly adrift: even if, as some claim, it's photoshopped, it's still right on the money

Now Obama is indicating that those with enormous wealth might reasonably be called upon to contribute a larger proportion of the tax that they might expect to pay if they didn’t have accountants. In this, he is in step with European politicians, even Conservative ones. In the light of the economic conditions under which most of us struggle, it seems a mild enough line to take. Obama clearly hopes to outflank right-wingers like Santorum and Gingrich who think economic salvation derives from private enterprise having the freedom to exploit and to reward itself disproportionately. Handily, it also undercuts Romney because Romney is so very, very rich – were he to become President, he would be the second richest man ever to enter the Oval Office (the richest was John F Kennedy).

And here I enter a note of caution. That American dream is still very potent. Millions of Americans – and not just right-wing fundamentalists in the south and mid-west – take the view that untold wealth might be just around their own corner, and if they could just get a break they would soon feature in the Forbes list. They know rationally that this is very unlikely to happen, that for every lucky son-of-a-gun who strikes gold there are thousands upon thousands who only sift soil and stones, including themselves. But they still dream and – in a notion that Obama will remember – they hope. It’s quite a universal impulse really. Europeans also subscribe to it when they play the lottery.

Gingrich sought to bring down Bill Clinton for sexual peccadilloes but is a notorious hound himself

It’s my contention that many Americans – the ones who, while they may not read or follow Ayn Rand, still revere the all-American maverick – are actually repelled by any idea that the wealthy should be, as the rich will claim, “soaked” or “punished” in being more heavily taxed. If you cling to a dream of untold wealth, your dream is tarnished by any suggestion that the IRS might then take it away again. So you don’t resent the other guy’s riches – good luck to him. Let him screw the government for all he can get.

Santorum wants less regulation, except in the bedroom

Barack Obama had better beware that he doesn’t characterise the wealthy paying a greater share in such a way that the Koch brothers are able to galvanise a wave of militant sympathy for the poor bloody rich to sweep through the Tea Party and wash a man whom that movement cordially loathes into the White House. It would be a poor Obaman legacy to find that his second term is supplanted by a chief who would be ripe for Dick Cheney-like manipulation on a grand scale, a hapless President Romney.

Yes, of course the best political entertainment this year has been the tussle for the nomination to represent the Republican Party in November’s US presidential election. Democrat Party supporters, the chattering classes and enlightened, informed people everywhere have pointed and laughed to scorn, while Barack Obama – no slouch he – has quietly got on with amassing the most gigantic electoral war-chest in global history and turning every public appearance into a stump speech.

The Republicans have no one to blame but themselves if they appear to be careering to defeat. Since the 2008 election, they have allowed the Tea Party and its bankrollers to annexe the GOP agenda and to muscle in on its choice of candidates. Both in their general demeanour and in the kind of candidate behind whom they have lined up, Tea Partiers have been blithely unafraid of looking like the lunatic fringe. Unhappily for them, this has paid diminishing returns as the months roll inexorably towards judgment day.

The Republican elephant – or possibly a mammoth

Candidates with uncompromising, irrational views tend to look wilder and flakier the more they are exposed to public scrutiny. And the unblinking attention of the media, even when it is that of Fox News, is merciless in cutting these numbskulls down to size. The Sarah Palin phenomenon seems to have burned out at last. Her successors as the darlings of the right – Michele Bachmann, Rick Perry, Herman Cain – quickly proved utterly inadequate to the task. Those still standing – Mitt Romney, Rick Santorum, Newt Gingrich and Ron Paul – have failed to gather irresistible momentum beyond their respective (and very distinct) core support.

Romney is the establishment choice, precisely because he isn’t a product of the Tea Party bubble. Like his father, George W Romney, he was a liberal Republican governor of a northern state (though Mitt stood down after one term) and, eerily repeating history, the son is also the front-runner in a race for the candidature but prone to hobbling his own case, just like the father. In 1968, George W allowed himself to be decisively overtaken by Richard Nixon. Unlike his father, Mitt has built ruthlessly on inherited wealth – George W was a self-made man -– and his financial ethics have been talked up as a potent liability by his Republican rivals, most usefully for the Democrats’ electoral machine. Mitt’s own uncanny knack for sounding the wrong kind of sang froid about his wealth and thus making his business success seem even more of a millstone may yet deny him the party nomination in August. A lot can happen in five months.

The Democrats' donkey (now retired)

It’s a curiosity of American iconography that the major political parties’ emblems are arse about face. The Grand Old Party presents itself as an elephant but its ability to forget – to rewrite history and move rapidly on – is unrivalled. The Democratic Party has dropped the donkey as its emblem, perhaps finally aware that it was ever incapable of delivering the donkey’s proverbial backwards kick. Since World War II, both parties have run with candidates who stood no chance – George McGovern (still around, rising 90) and Fritz Mondale for the Democrats, Barry Goldwater and Bob Dole for the Republicans – but the ferocity with which the doomed candidate’s party rivals slug it out cannot be compared. For instance, the story of George W Romney’s opposition to the candidacy of the right-wing fundamentalist Goldwater in 1964 is worth seeking out. Mitt lacks Dad’s killer instinct.

Not so great after all: the other George W

When it comes to the crunch, the Republican Party – like Britain’s Tories – is most always mindful of its own best interests and ruthless in the despatch with which it divests itself of a candidate it knows cannot win. Don’t discount the possibility of someone not now running being drafted to rescue the cause. In this campaign, the GOP has faced an unprecedented dilemma because the immeasurable power of the Tea Party makes everything so uncertain. The invisible Koch Brothers, without whose billions the Tea Party would be nothing, exert huge power but lack the practical political skills to see what both the immediate and the long-term effects of that power might be. And the Washington elite has not had to deal with such incoming power before. There is no roadmap for what is going down.

In a provocative assessment, widely circulated, George Monbiot credits the eccentric Russian émigrée writer Ayn Rand (who died thirty years ago this month) as the source of much current right-wing philosophy in the US. I do not doubt for a moment that Rand has had her adherents – many of them, intriguingly, in Silicon Valley – but Monbiot quotes a Zogby survey (which I cannot locate on the internet) to the effect that one American in three has read Rand’s notorious philosophical treatise, Atlas Shrugged. I apologise – disputing with George Monbiot is not to be undertaken lightly – but one-third of the US has certainly not heard of Rand, let alone read her. I should be more persuaded by a finding that one in three Americans has not read a book of any kind since leaving high school.

Atlas Puffed: Ayn Rand

Rand was undeniably influential – let’s not forget that Alan Greenspan, who ran the Federal Reserve for twenty years, was a close protégé – but in terms of public recognition she was no Oprah Winfrey. She constructed her own slant on the American dream but she did not originate or even embody the articulation of that dream. James Truslow Adams’ 1931 treatise Epic of America attempts a summary that still serves: “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement … It is not a dream of motor cars and high wages merely, but a dream of social order in which each man and each woman shall be able to attain to the fullest stature of which they are innately capable and be recognised by others for what they are, regardless of the fortuitous circumstances of birth or position”.

The peculiar contribution Rand made to the dream was to argue that opportunity and attainment are constrained by regulation and concern for others, that the American dreamer should shrug off the pettifogging attentions of authority and government and the finer feelings of his neighbours and ruthlessly pursue the dream. It was a more incisive spin on a staple, age-old figure from American myth and literature, offered again and again to the public especially through the medium of cinema: the romantic individualist, the maverick, the heroic outlaw, the lawman who breaks all the rules, the righteous man of action.

Mitt marries his Ann, 1969

Truslow Adams perceived that the American dream was inherently a repudiation of European class and caste, hierarchy and inheritance. In the American dream, all might rise – in the pre-feminist legend, any boy could grow up to be President – and birth, school, club and all such masonic connections would count for nothing. Rand took this further, preaching that community and social interdependence also counted for nothing. There is a clear echo in Margaret Thatcher’s famous retort during a 1987 interview for Woman’s Own: “[people] are casting their problems on society and who is society? There is no such thing! There are individual men and women and there are families. And no government can do anything except through people and people look to themselves first. It is our duty to look after ourselves and then also to help look after our neighbour”.

Santorum: "Some gay men are this big"

Barack Obama has been widely “accused” of being a Socialist – not, of course, by Europeans who know what a Socialist is, but by Americans. That is because Obama has made a few small gestures towards trying to relieve the plight of the poor and the unemployed and those who cannot afford health cover. Even with the prevailing philosophy of the post-Blairite governing class in Britain, wherein more and more social provision is either outsourced to racketeers or withdrawn altogether, Obama’s achievements look small beer. By a rich piece of irony, Mitt Romney introduced health care measures in Massachusetts during his governorship that in many ways provided the model for Obama’s federal health care reform of 2010. Romney is no more a Randian by nature than is Obama.

The letters of 'Mint' Romney's name come sadly adrift: even if, as some claim, it's photoshopped, it's still right on the money

Now Obama is indicating that those with enormous wealth might reasonably be called upon to contribute a larger proportion of the tax that they might expect to pay if they didn’t have accountants. In this, he is in step with European politicians, even Conservative ones. In the light of the economic conditions under which most of us struggle, it seems a mild enough line to take. Obama clearly hopes to outflank right-wingers like Santorum and Gingrich who think economic salvation derives from private enterprise having the freedom to exploit and to reward itself disproportionately. Handily, it also undercuts Romney because Romney is so very, very rich – were he to become President, he would be the second richest man ever to enter the Oval Office (the richest was John F Kennedy).

And here I enter a note of caution. That American dream is still very potent. Millions of Americans – and not just right-wing fundamentalists in the south and mid-west – take the view that untold wealth might be just around their own corner, and if they could just get a break they would soon feature in the Forbes list. They know rationally that this is very unlikely to happen, that for every lucky son-of-a-gun who strikes gold there are thousands upon thousands who only sift soil and stones, including themselves. But they still dream and – in a notion that Obama will remember – they hope. It’s quite a universal impulse really. Europeans also subscribe to it when they play the lottery.

Gingrich sought to bring down Bill Clinton for sexual peccadilloes but is a notorious hound himself

It’s my contention that many Americans – the ones who, while they may not read or follow Ayn Rand, still revere the all-American maverick – are actually repelled by any idea that the wealthy should be, as the rich will claim, “soaked” or “punished” in being more heavily taxed. If you cling to a dream of untold wealth, your dream is tarnished by any suggestion that the IRS might then take it away again. So you don’t resent the other guy’s riches – good luck to him. Let him screw the government for all he can get.

Santorum wants less regulation, except in the bedroom

Barack Obama had better beware that he doesn’t characterise the wealthy paying a greater share in such a way that the Koch brothers are able to galvanise a wave of militant sympathy for the poor bloody rich to sweep through the Tea Party and wash a man whom that movement cordially loathes into the White House. It would be a poor Obaman legacy to find that his second term is supplanted by a chief who would be ripe for Dick Cheney-like manipulation on a grand scale, a hapless President Romney.

Sunday, March 04, 2012

LAST POST

For the five or six generations of solitary, sedentary boys in the middle of which fell my vintage (the baby boomers), the hobby par excellence was collecting stamps. Philately, as we preferred to call it, could be enjoyed alone on a long winter evening or with others, particularly when engaged in the cut-throat business of “swaps”.

There were plenty of tangential benefits that surely trumped whatever – other than burning off energy – was to be gained from being out playing football or cowboys and indians. Stamps from abroad opened up foreign parts in a unique way at a time when television was still in its infancy. Significant events and figures from the diverse pasts of diverse nations were apt to be commemorated on stamps. Present national and international events were marked also, and culture, science, industry and other important enterprises were reflected on postal issues. Finally, the philatelic artwork itself gave one an appreciation of design and the particular skills of miniaturisation. So a stamp collection was a guide to geography, history, art and current affairs in little. It did just what John Reith’s BBC was designed to do: educate, inform and entertain.

A typical Commonwealth issue of the kind 1950s little boys collected

Like most collectors in that period, I began with British and Commonwealth stamps, the ones most readily available on envelopes that came through the door. But I was drawn to European stamps, so many of which had an elegance you didn’t find in the rather drab and restrained home issues. Then I had a lucky break.

My mother had golfing friends who turned out to have a serious stamp collection. The husband, Henri Castel, was a Frenchman who had been brought up by an English guardian: there were intriguing rumours of an improper relationship. Henri was glamorous and charming with thick, black, wavy hair and a Günter Grass moustache. The little finger was missing from his left hand: in his account, it had been bitten off by a horse when he was serving in the cavalry. I happily swallowed this version. He seemed to me a hugely romantic figure and I was hopelessly smitten.

No less glamorous – if a little forbidding for my taste – was his German wife Hildegard. Everyone remarked upon her facial resemblance to Dietrich, although in truth this was a touch far-fetched. Nevertheless, a German woman living in an English market town less than a decade after war’s end was, to say the least, something of a novelty, and if, by relating her to an acceptable German, the locals found a way to accept her, so much the better.

Hilde’s father had possessed a huge and – I would hazard – internationally significant collection of German stamps that, some time in the early years of the cold war, Henri and Hilde managed to smuggle piecemeal out of East Germany and bring to England. These were the treasures to which Henri introduced me during our regular Saturday mornings at his parlour table in their beautiful townhouse. With a generosity that, in retrospect, makes my head spin, he passed to me many fine items from his own and his father-in-law’s collections.

The Reich Chancellor at his peak

With Henri’s encouragement, I built my own German collection. Hitler remained a palpable bogeyman for several years after the war and there was a curious frisson in owning miniature portraits of him issued in the years of his pomp. There was no sense, though, that Henri and I were keeping some flame alive. Far from it. We were dealing objectively with the historical objects that happened to be available to us. For a school open day, I prepared a potted history of twentieth-century Germany illustrated with stamps from my own collection. By mutual consent, Henri gave me no assistance with this, save for his comprehensive enthusiasm when it was finished and ready to show. I duly won a prize.

My own instincts embraced French and Dutch stamps quite as much as German, and Henri helped and encouraged these parallel collections. As with any collecting field where the items are contemporary as well as historical, the new issues need to be systematically added if the collection is to remain sharp. Though I had built serviceable historical cores to my collections, the various intrusions attendant upon growing up prevented my keeping them up-to-date. The Saturday morning sessions dwindled. I suppose I was eight when they began and twelve when they ended.

The Castels had slipped away from the centre of my life when my mother told me that Henri had dropped dead on the golf course. I remember that my emotions were curiously detached, that I had somehow sensed that such a treasured mentor would be snatched away. I guess I was then about 16, Henri probably in his early 50s.

I still have the stamp collection. Would it be worth anything? Collecting is very subject to the vagaries of fashion and to quite external factors. In a world where so much of what we deal with is digital, stuff that you can hold is less favoured, but that may not always be so.

An archetypal French classic

I have added little to the German, French and Dutch collections for years. But I have systematically kept my British collection current by purchasing the new stamps as they were issued, a set to keep mint, another to post to myself so that they acquire postal franking. Though the Royal Mail makes a great fuss about the delights of philately and puts out special issues in ever increasing numbers, most of the management decisions made concerning postal services over the past couple of decades have militated against the collector.

British stamps were graphically modest and infrequently issued before the 1960s. Then suitable occasions for special issues began to be found: the Post Offices Savings Bank centenary, the European Postal and Telecommunications Conference, the ninth International Lifeboat Conference. In 1964, the first commoner was depicted on a set of British stamps when the quatercentenary of Shakespeare’s birth was marked. By this time, a modernist was overlord of the postal service.

The post of Postmaster General dates back to 1823 and it had cabinet rank. Among distinguished PMG’s were Austen and Neville Chamberlain, Clement Attlee, Charles Hill and Ernest Marples. The last holder of the office, before it became Minister of Post and Telecommunications outside the cabinet in 1969, was the notorious John Stonehouse.

From 1964 to 1966, the PMG was the MP then known as Anthony Wedgwood Benn. At this time, the organisation was called the General Post Office (GPO) – my mother used to say “I’m just going down to the General”. The GPO was a government department and, as its effective chairman, Tony Benn greatly expanded the scope of commemorative stamps and encouraged the recruitment of contemporary graphic artists.

A special stamp of 1966, yet to be updated

New structures such as the Forth road bridge and the GPO tower were depicted and the first themed set, of British landscapes, was issued. The death of Churchill was marked – a real departure this and not without controversy – and a third commoner, the poet Burns, was celebrated. The battles of Britain and Hastings were memorialized and (another populist touch) the football World Cup, which England hosted, was the subject of a set, followed by the rush-release of an amended stamp to mark England’s win. Finally, 1966 saw the first issue of Christmas stamps, an annual treat ever since.

The art of postage stamp design, with a few vulgar exceptions, has been upheld by successive manifestations of the postal service until quite recently. In 1969, the GPO ceased to be a government department and was converted into a nationalized industry. Twelve years later, it was divided into Post Office Ltd and British Telecom, the latter of which was subsequently privatized.

The division of the telephone service from the postal service had an immediate and deleterious effect. Vandalism of public phone boxes had become epidemic but you always knew that you could find a working callbox inside a post office. With the split, public phones were ruthlessly ripped out of post offices and, until mobiles made the callbox redundant, finding a working phone was even harder.

What is now called Royal Mail Group is a public limited company wholly owned by government. At vast expense, the group changed its name to Consignia about a decade ago, then paid belated attention to what everyone told it and, at more vast expense, reverted to the title Royal Mail. This absurd gaffe, over which no resignations were evidently required, is an indication of the sorry state into which the administration of the postal service has steadily plunged.

The motto of the Wells Fargo company was “the mail must get through”. Whether by stagecoach, steamship, railroad, pony express or telegraph, Wells Fargo delivered the fastest way. Much more than the post service in Britain, the US mail was a mission, a crusade, an absolute. It remains true. Go to New York’s main post office by Madison Square Garden: its customer service is a model of its kind.

There’s a celebrated legend carved on the frieze of the New York post office: “Neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds”. My American friends report that this is not exactly an accurate account any longer, however. Mail between the UK and the US does get through in good time; but internal US mail is notoriously delayed.

A First Day Cover, another Royal Mail scheme to squeeze income from collectors: FDC's are too schematic and unwieldy for my taste

The UK post has perceptibly declined in my lifetime; it has also lessened at each of its government-decreed changes of status. In my childhood, any item posted early in the morning to an address in the same town (or marked ‘local’) would without fail arrive by the second delivery the same day. If a parcel were too big to be accommodated by the letter box or it had to be signed for, the GPO would move heaven and earth to get it into your hands at the earliest opportunity, calling round again and again until they found you at home or coming to some arrangement with a neighbour.

None of this survives. The second delivery was never a fully national service. Sydney Smith, the great clerical wit whose life only extended into the Victorian era by eight years, loftily dismissed a rural retreat he had visited as “a place with only one post a day … in the country, I always fear that creation will expire before tea-time”. But second deliveries everywhere died out some years ago. In 2004, the Royal Mail announced the formal end to second deliveries. “Some customers will see little or no change to their current delivery times” claimed a round robin over the signature of the Sales and Customer Services Director. Indeed, daily deliveries were by then so delayed, especially in London, that they arrived later than second deliveries had done a generation earlier.

Thereafter, our post in the west country arrived some time between 10:30am and noon, extending now to as late as 2:30. I hate it. Until 2004, I was wont to open the mail with my breakfast. Now, because the moment has passed, it gets left unopened in my study, sometimes for days on end. Bills go unpaid and reminders get issued. Special offers expire. Replies to the few personal letters that now arrive are tackled later than I would choose.

More important than all that, the sheer pleasure of receiving post has withered away. And how disappointing not to get your cards before departing for school on your birthday. It is inevitable that email has supplanted letter post. I can read an email within moments of its birth. That’s a big plus, of course. But there are down sides. With a few exceptions, the writer will have dashed off the email and not read it through so it will be strewn with errors. And it almost certainly will not get bequeathed to Harvard. Shall future generations be treated to fat volumes of The Collected eMails of Will Self or The Annotated Texts of Paris Hilton? I doubt it. But unlike the scorned “snail mail”, it does get through (technical glitches permitting).

Without announcement, the Royal Mail abandoned another part if its service in 2003, a part more subtly significant. It tore up its collection timetable. For decades, postwomen and men emptying postboxes had diligently indicated so doing by changing a small white enamel square slotted into the box’s face just above the posting aperture. So, if you arrived at the box to post your letter and the black numeral on the enamel square said 2, you knew that you were in time for the second pick-up at (say) 11.15am, as indicated on the timetable displayed on the box. This was critical for attempts to catch early collections whereby you confidently expected next-day delivery.

A Christmas FDC issued from the Welsh village of Nazareth

With the timetable gone, the enamel squares went too. Now you could not tell if the box-emptying had been performed to time. In fact, there was nothing to say that the box had been emptied at all, let alone when it was emptied. All that was displayed was a formal last collection time and, as I soon discovered by occasional observation of the postbox nearest our house, this time was a mere approximation and might be missed by twenty minutes or more either way. So you might post a letter at 5.35pm, expecting it to be collected at 5.45pm (as advertised) and so be on its way that day to its destination, unaware that the collection has already been made at 5.25. And your letter was still lying there, perhaps until after 6.00pm the next day.

In the face of evidently influential criticism, the post office did restore a crucial part of the publicly revealed timetable. Now the boxes at least carry a square indicating the day on which the next collection will take place. So, if it announces ‘Wed’ when you post your letter at 5.47pm on Wednesday, you can hope that it will be collected shortly. Whether there is any more than the one advertised ‘last’ collection each day, we cannot guess.

Of course, as a public concern, the Royal Mail is damned if it does and damned if it doesn’t. Sustain a loss – £120m last year – and it’s inefficient and a drain on public investment. Make a profit and it is creaming it at the public expense. The only way the company can win back its good name is to break even by performing efficiently. If the public feels that it is dependable, whether it turns profit or loss is secondary. Meanwhile, successive governments’ fetish for privatization will ensure that Royal Mail loses its most profitable services to ruthless competitors.

From my philatelic point of view, the 1950s and '60s made up a rosy era. Every tiny village had its own circular date stamp (CDS) with its name included. In philatelic philosophy, CDS’s were thought much the most preferable franking on a specimen that was termed ‘used’ (which is to say franked and then soaked from the envelope, allowed to dry and mounted on a gummed hinge in an album) as opposed to mint (unfranked and with its full original gum on the reverse and so preserved in a slip-in album). I favoured used stamps for, unlike the pristine and rather soulless mints, they had seen life.

You soon learned where the franking machine was most likely to deposit the postmark on the envelope, so you could position your stamp to catch the CDS. In any case, much franking was still done by hand and, as postal staff looked in a kindly way on stamp collectors, the hand franking was usually performed with care. In order to give my collection variety, I got into the habit of posting stamps to myself on trips away from home (or persuading others to do it for me) so that the places franked onto the stamps were many and various.

Queen drummer Roger Taylor made history in 1999 as the first identifiable living commoner not marrying into royalty to appear on a British stamp

Eventually the Post Office saw that the franking could provide a promotional opportunity. Accordingly, slogans began to appear alongside the CDS’s – POST EARLY FOR CHRISTMAS was a famous one. For a while, even commercial advertising was permitted but I suspect that firms found the variable legibility of the messages something of a liability and this was dropped.

But changes in methodology rendered posting stamps for franking a less and less satisfying method of building one’s collection. Postal depots closed down and mail travelled ever longer distances to be sorted. The localities with their own franking identity dwindled in number. Now they encompass whole cities and counties, even regions. Most depots have installed inkjet printing, which does not use CDS’s at all but simply franks a city or county name and a date.

And the Royal Mail no longer has any feel for stamp collectors’ wishes. When I first lived in London, I shopped for new issues at the block-long post office in St Martin’s Place. Its philatelic department was a whole wing with its own entrance, and its staff handled the stamps wearing white gloves. But that was long ago. The philatelic dept became a Prêt and collectors’ concerns are dealt with at one window on the main strip. Elsewhere, all the philatelic counters that used to serve collectors in large post offices outside London have closed. The only way to be sure of obtaining all the new stamps is to pay regular visits to St Martin’s Place or to order by post from the Philatelic Bureau in Edinburgh.

The number of new stamps has burgeoned. There have already been thirty-four (34!) issues to mark the imminent London Olympics/Paralympics. The Queen’s Diamond Jubilee will add substantially to the understandable but still huge accumulation of issues featuring the royal family past and present. Miniature sheets and multi-page booklets of otherwise unavailable stamps add to the cost for the collector who is a completist.

The entirety of special issues for the London Olympics of 1948

As for franking, if the machine misses a stamp, nobody cares and the envelope is delivered without franking. In recent years, I have been obliged to post the same envelope seven, eight, nine, even a dozen times to secure a franking. Worse, some misanthropic sorter will blithely score through the stamp in biro, rendering it useless as a collectable item. As the stamps I post to myself are priced well in excess of the amount required for postal use, the philatelic aim of the posting is obvious. That some sorters take a perverse pleasure in spoiling the stamps is clear, for they sometimes wield their biros even if a stamp has been successfully franked.

One of the sets issued ahead of the 2012 Olympics

I wrote to the Royal Mail’s official organ for stamp-collectors, the British Philatelic Bulletin, about this disheartening development. My letter was passed to Royal Mail Customer Services, whose agent’s response could be summed up with the word “tough!” At any rate, she felt that the matter was “outwith the control of Royal Mail” – the use of “outwith” indicates that Royal Mail headquarters is in Scotland. It seems it is possible to send one’s stamps under separate cover for franking with pictorial images that are permanently available but such a service thwarts the desire to have a collection that looks authentic, as well as adding substantially to the cost of collecting. (Anyway, there’d always be some bugger at our local depot who decided to spoil my stamp with its special franking, just for the pleasure of it).

And now Royal Mail has delivered the coup de grâce. At a time when we are all obliged to economize – some of us more than others – the proposal to send the price of stamps through the roof is the last straw. The plan is that first-class post should rise from 46p to a minimum of 50p – and Royal Mail would prefer a lot more. Even this minimum rise is 8.7 percent or 5.1 percent above the inflation rate. Of course other postal rates would follow suit.

With competition pressing in from every side – private enterprise delivery, digital communication – Royal Mail appears to have decided that suicide is the best course. The only unique aspect that remains is the philatelic one. But as Royal Mail prices itself out of the postal market, so it is squeezing collectors out of the hobby. I for one simply cannot afford to avail myself any longer of the combination of the glut of issues and the dwindling of attention to collectors’ needs. After nearly sixty years of pleasure, I am giving up stamps.

For the five or six generations of solitary, sedentary boys in the middle of which fell my vintage (the baby boomers), the hobby par excellence was collecting stamps. Philately, as we preferred to call it, could be enjoyed alone on a long winter evening or with others, particularly when engaged in the cut-throat business of “swaps”.