A GHOST STORY RETAILED

ACT I: LITTLE SHOPS KNOW HORROR

The narrative arts are apt to organise their material into three acts. The first sets out the status quo – the situation, the characters, the mise en scène. The second introduces development – change, challenge, conflict. The third offers resolution – a return to the status quo (the sentimental happy ending) or, in more mature work, a new and perhaps superior accommodation or a reluctant reconciliation or a new realism.

Real lives are lucky if they ever reach a third act. Most of us spend our youth finding out who we are and the rest of our adulthood more or less regretting that precious little of what we found out in youth may still be relied upon. This pattern is so common and predictable that you would think the human race might have devised strategies for dealing with it by now. But no. As with walking and talking, so every generation has to learn anew that there are no eternal verities and that our projects and prospects are grand edifices built on foundations of balsa wood.

Take shops. Even twenty years ago, it would have seemed unimaginable that the retail parades around which every community of any size grew up in Britain as elsewhere would now be well into a long and slow but evidently irrevocable decline. If you’d asked people half a century back what would be going strong and confident a decade into the next millennium, they might not have cited the trade union movement or the nuclear family or the railways or horse-drawn traffic or the bobby on the beat or the British Empire or the printed newspaper, but they surely wouldn’t have marked the high street as one for the bonfire of history.

Fifty years ago next year, my father closed for the last time the factory that he had managed for most of three decades. The story of the secret takeover of the business by city slickers who eventually went to jail is a yarn for another day. But Dad had known only one trade – boots and shoes – ever since he left school at 14 and it was clear what he must do. Aged 50, he drew the dole for precisely one week and then opened a shoe shop: Stan Gilbert Footwear Ltd.

It was hard going. Footwear was the county trade and everyone for miles around had a family member who could get hold of free or at least cut-price shoes. My mother and I worked long hours to help – I was a teenager – and, by degrees and shrewd use of trade contacts, Dad made it pay and survive for twenty years. It helped a lot that, though a narrow, unimaginative and prosaic man, he was transformed into a poet with a well-made shoe in his hands. The first pair that I owned as a child was wholly fashioned by him, by hand, from scratch. I still have the lasts on which he made them.

Aside from the product, no one had to teach my father (or indeed my mother and me) the rudiments of serving behind the counter. That was what it was – a service – and we knew it when we received it, which was pretty much everywhere when shopping. We all lived instinctively by Gordon Selfridge’s dictum: “the customer is always right”. No task came before attending to a customer; and shops, especially independent ones, generated dozens of tasks, some daily, some weekly, some seasonal (the annual ritual of stock-taking was a real three-ring circus). Anything that might interfere with one’s readiness to serve a customer was done before the shop opened or after it closed. Everything had to be in place at opening time. Nobody stacked shelves or cleared the till or (unthinkable!) yakked on the phone while there were potential spenders on the premises.

My father had his particular ways of doing things, but most of what we all did as retailers was to reproduce what we knew from our own shopping. So you called customers ‘Sir’ or ‘Madam’ (even if mere teenagers), or you addressed them as Mr or Mrs So-and-So if you knew them (in a medium-sized town, those you knew by name made up a high proportion of your trade). You judged how far they wanted to browse unhurriedly, whether they might demur at the offer of assistance, when to clinch a sale and when to wait for them to reveal an inclination. There were always time-wasters, those who came in for a warm or a chat or to pass the time of day, those who wanted to check your stock or were just nosy about what you had to offer. In a one-trade town, there might also be the low-level equivalent of industrial spies who popped in for a quick shufti and reported back to a rival. All of these you treated with the greatest courtesy, restraint and patience. The customer was always right.

When they found nothing that suited, you described the lines on order and what might be in soon. You never let them leave the shop feeling that you were indifferent to their custom. When they made a purchase, you showed them the price tag and offered a shoebox and/or a paper bag to carry them in. If they made more than one purchase, you added up the prices in your head and checked your calculation against the till when you rang up the amount. You took their money (keeping notes in view until the sale was complete so that they couldn’t dispute the denomination they had tendered) and – absolutely standard, this – you counted the change coin by coin, note by note into their hand. (When I worked in a bookshop in the early ’90s, I found that the by-then novelty of counting out change was greatly appreciated by the customers). You gave them a receipt, thanked them kindly but not profusely and hoped to see them soon. You certainly didn’t remark “brilliant!” just because they’d had the gumption to pay for their purchase.

By the by, prices even then were generally one penny below a round figure – for instance, 19/11 (that’s 19 shillings and 11 pence which is the equivalent of 99.5p today). The reason for this sort of pricing was not to bamboozle the customer into imagining that the price was a lot less than £1. It was to oblige the shop assistant to open the till to make change, given that passing few customers would be carrying exactly 19/11. Hence the transaction would have to be recorded on the till and the shop assistant could not pocket the money and keep the sale a secret from the shop owner which, when the correct money – say £1 – is tendered, is perfectly possible.

Something else to note about Dad’s shop is that he only sold shoes and a few strictly footwear-dependent items, like laces. He didn’t stock phone cards (remember those?), DVDs, lottery tickets, postage stamps, bunches of alstrœmeria or sandwiches. He wasn’t part of a chain so he determined his own prices; several he marked down as loss leaders, cutting profit margins to encourage a higher volume of sales. He didn’t have piped muzak in the shop.

In those days, all transactions were made by cash or cheque. No one had credit cards. Hire-purchase (known as ‘the HP’: payment by instalments) was much more widespread and, when money was tight as it was for many in the post-war years, people would ask if they could get things on account. Indeed, many shops (though not Dad’s) displayed signs that read: “Please do not ask for credit as a refusal often offends” (yes, really). I recall a fish-and-chip shop owner crossly turning to me, then just a boy of seven or eight, to tell me that his previous customer, a young woman leaving as I was arriving, had had the nerve to ask for “sixpenn’th of chips on tick”.

Premises like Dad’s, the founding stones of the high street, have been swept away. The phenomenon of the sole-proprietor shop has dwindled to a vestigial few. This is partly due to their drift from true notions of service and specialist expertise. Further, the family business notion was eroded by myriad factors – among them, more mobility and awareness of other options, less deference and sense of obligation to parents. As young people learned to aim for further education, seeing the world and moving away from the limitations of a small town, they were less attracted to the idea of working in and eventually running Dad’s ailing jewellery shop or the green grocers’ staffed by successive generations of brothers and sisters.

While these little shops died, the small and medium-sized chains struggled too, not without their own casualties, Woolworth’s and Habitat being, I suppose, the best-known and most mourned. The survivors all look rocky when even the pre-Yule rush never properly materialises. Unthinkable just a few seasons ago was a sight that greeted us on our own high street this year: the Oxfam shop having a sale throughout the very run-up to Christmas.

Much, much more responsible for the death of independent retailing and the decline of the high street has been the relentless advance of the behemoths. I’ll come onto the superstores in another posting, pausing merely to remark here that through their bulk buying and preferential access, their bullying and their undercutting, the supermarkets force all the smaller, more specialist shops to the wall.

Consider an area of the market of particular interest to me as a sometime journalist. It is only relatively recently that the big stores started to stock newspapers and periodicals. They began with the national dailies and a few television and women’s magazines. When this worked well, they expanded their displays to include pretty much everything at the popular end of magazine publishing, the stuff that is an easy sell. They aimed to catch the impulse buyer who spots a headline or a strapline or who always meant to take a look at Heat or Hello! (there must be such people). They also entice the shopper happy to pick up a paper or a TV Choice without bothering to go to the newsagent’s. But with the more specialized publications the supermarkets naturally do not bother. That would mean supplying a service and going to trouble for specific customers rather than snaring random, passing trade.

The independent newsagents do carry arcane magazines or order them for regular customers. But the supermarkets have cut a vast swathe out of the newsagents’ main source of income: newspapers, popular magazines, soft drinks, sweets and cigarettes. As one after another newsagent goes out of business, the specialist magazines that depend on them for their sales lose their outlets. So their narrow profit margins are squeezed until they too fold. And that’s the death of another source of income for a writer like me.

Our one-time newsagent in north London told us how he would walk past the local supermarket on his way to open his lock-up shop at some unearthly time in the morning. The supermarket would be closed for hours yet but its stock of newspapers was already waiting tied in bails at the door. His supply, however, would not be there when he opened; it would turn up at some unpredictable juncture after many customers had left empty-handed. Every independent newsagent has the same experience; multiply that across the nation. Great! What a clever ploy of the newspaper distributors to favour the big boys even though it loses them precious, dwindling sales.

Stocking papers and popular mags is just part of the move to diversify that has comprehensively disfigured the retail trade. Now everybody stocks everything. How I long for an age when shops did one thing surpassingly well instead of lots of things in a mediocre fashion. I am so old that I remember when Boots was a chemist’s.

As with so many other baleful developments, television played its part in the retail trade’s decision to spread itself thin. For the item that was seized on by the widest variety of shops was the newly desirable videotape in the late 1970s and early ’80s. Far more than in any other country, home taping took serious hold in Britain from the moment VCRs hit the shops. And, while only large or specialist shops could hope to make a go of selling movies on tape, blank tapes could be sold by anyone; and they were. Early in the ’80s, we came across a peculiar combination in Exeter, a chippie selling videotapes. He called himself Fish’n’Flicks. Somehow, I didn’t fancy buying a videotape misted with the spray of chip fat: how much damage would it do to one’s recorder? I hardly imagine that he’s still in business, not at any rate for tapes.

The ubiquity of tape has long since been overtaken. Indeed, for a Luddite taper like me (I have way too many stored videos to change now), blank tape is almost impossible to find and the odd but (for me) useful lengths extinct: 120, 195, 210, 300 minutes. I could only be sure to find any blank tapes locally in a video shop whose prices were the highest I had encountered in more than 25 years. But it’s closed down now. Inevitably, one is driven to rely on internet shopping for tape.

The diversification into unrelated goods roared on. In the wake of tape, petrol stations started selling food (even less appetising than fat-sprayed videos), butchers sold cheese and eggs, post offices stationery and greetings cards, bookshops DVD’s and coffee, lighting shops furniture (we once bought an occasional table at Christopher Wray’s), florists ceramics and knick-knacks and so on. Were Stan Gilbert Footwear still going, I suppose he would have to major in trainers and offer sidelines in handbags, luggage, socks, roller skates, skis, hiking maps and ointments for athlete’s foot.

Superstores now routinely stock supposed fashion, down-market books, toys, bed linen, firewood and electrical goods and offer dry-cleaning, insurance and banking. Surely coming soon to your local Asda will be: ayurvedic massage, care for the elderly, tarot readings, dog-training, escort services, yoga, line-dancing classes, personal bodyguard hire, pro bono legal advice, endangered species as pets, landscape gardening, group therapy, dentistry, armaments for any eventuality, car boot sales and cosmetic surgery while-u-wait. (I’m joshing but you’ll tell me of any branches that do indeed offer some of these). Such vast diversification by the stores with limitless pockets puts pressure on every small business to augment the line that was once a matter of expertise and comprehensive service.

When I moved to London to become a university student, I found a city crammed with fascinating stationery shops. I soon learned where to buy those left-field items that any writer relishes: typing paper in quarto size (handy for short letters), box-filing cards in quantity at a reasonable price, two-tone typewriter ribbons, varying shades of carbon paper, all kinds of covers for manuscripts and documents, a vast variety of graph and ruled paper, felt-tipped pens of the idiosyncratic style that I favoured.

It couldn’t last. Along came a chain called Ryman’s that one by one squeezed all the individual stationers out of business. Ryman’s stocked none of those quirky items that I so liked and they killed off the shops that did stock them. I loathed Ryman’s. One day, passing a branch, I caught sight in the window of a neat little photocopying machine designed for a small office. I had always dreamed of such an addition to my workspace. Taking a deep breath, I crossed the hated threshold and soon emerged carrying the photocopier. It was indeed so light that I carried it home on foot. What a fool for making an impulse purchase from the enemy. The copier never worked reliably and, when I ran out of paper for it, I found that the particular paper it required was grotesquely expensive. Only Ryman’s stocked it and they dropped it not long after. And the rule with a chain is: when head office cancels a line, no branch carries it. I knew it was futile to protest at the branch where I bought the damned thing.

The last time I was in London, I found that the one great independent stationer’s left, Osman’s of Wardour Street, had finally but inevitably gone. The death of the stationery specialists, along with the decline of newspaper shops (whose trade has also been hard hit by the reduction in demand for smoking materials), is just a small symptom of a much greater malaise: the death of variegated retail.

Part of the process of decline of the high street was that every town centre became identical to every other town centre because the major chains were the only retailers who could afford the rentals. Nor is it just the case in Britain. Go to towns and cities in Europe and even further afield and the same fascias gaze down upon you from shops that used to be unique and local.

And as the small independents died, what was striking was how the most likely new tenant was a hairdresser’s, a “beauty salon”, a bistro or a fifty-kinds-of-coffee hangout. In country towns like the one nearest us, the other most prolific businesses – at least until the recession set in – were estate agents.

In taking over and standardising town centres, some of the chains overreached themselves and found that they had to cut back again. Even some of the superstores fell back and Safeway and Somerfield are gone. I certainly don’t miss our local Somerfield. On the few occasions that I found myself driven to enter it for lack of any more desirable shop, it was hopeless. The prominent “ten items or less” sign at one of the checkouts was never enforced and I never saw the so-called “express checkout” actually open. I used to refer to the place as Slumberland. It’s now a branch of the Co-op and, as far as I can tell, not much better.

Ah yes, the superstores … TO BE CONTINUED.

Saturday, December 31, 2011

Wednesday, December 21, 2011

ONCE in UNREAL DAVID's (BIG) SOCIETY

The Prime Minister has declared Britain “a Christian country … and we should not be afraid to say so”. It’s not unusual, of course, for politicians to make assertions that have no basis in fact. Sometimes this is done out of ignorance, sometimes out of dishonesty, sometimes out of self-denial, sometimes out of malice, sometimes out of hubris, sometimes out of simple foolishness. It’s hard to know which – if not all – of these is the wellspring of Cameron’s announcement. But, whichever way you cut it, it is not true.

In the most recently published results of the British Social Attitudes survey, those accounting themselves as Church of England were below twenty percent. Non-denominational Christians were under ten percent and Catholics less than nine percent. Those who said they had no religion of any kind numbered a little over fifty percent. In other words, Britain is not even half a Christian country. Indeed, considerably more people are certainly not Christian than voted for the parties comprising the coalition government. For whom does Cameron believe he is speaking?

Cameron's Christmas cards don't do religion: this was last year's, emphasising his parental orientation

Given that he must know – his advisors anyway must have pointed out – that his claim would likely alienate and repel rather more listeners than it would please (and besides, those pleased would be overwhelmingly dominated by those whose support is already assured), what did he think he was up to? Can he have been fending off in a subterranean way those filthy foreigners in the non-C-of-E European Union: Catholic France, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Poland and Ireland, Lutheran-Calvinist Germany? Could it have been a low piece of point-scoring against the Jewish Ed Miliband? Was it a crude attempt to identify himself with the spirit of Christmas? If this latter, he’d have done better by volunteering to switch on the lights in Oxford Street or accepting a cameo in the Christmas Day editions of either Downton Abbey or Absolutely Fabulous. The seasonal worship indulged by the vast majority of the British electorate is of those great gods, Retail and Telly.

The obvious question arising from Cameron’s asseveration is: does this supposedly Christian nation have a Christian government? Well, let’s just consider how far it measures up to the more obvious of Christ’s teachings and tenets. To begin at the beginning: “I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” [Matthew 19:24]. Two-thirds of the Cabinet are millionaires, several of them (including Cameron) multi-millionaires. So ministers – all of them, it’s fair to say, because even the non-millionaires are rich by most people’s standards – are booked for eternal damnation; which rather reduces their credentials as Christians, wouldn’t you say?

On the subject of damnation, Matthew has another pertinent passage for this government: “Then shall [God] say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels:/For I was an hungred [i.e. hungry], and ye gave me no meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink:/I was a stranger, and ye took me not in: naked, and ye clothed me not: sick, and in prison, and ye visited me not:/Then shall they also answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, or athirst, or a stranger,or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister unto thee?/Then shall he answer them, saying, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me” [Matthew 25:41-5].

You notice how Christ does not suggest that we are all in it together or that helping the deprived is too expensive because of the “mess” that God inherited or that there needs to be a “stranger” quota, at least among those from outside the European Union. It is a given that the “least” must be “ministered” to. Neither does Christ suggest that the top rate of tax ought to be lowered. The government clearly does not subscribe to the philosophy as expressed here in Matthew’s account.

The government’s constant harping on eliminating the deficit puts it on the side of the Pharisees whom Christ excoriated: “Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye pay tithe of mint and anise and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone./Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel” [Matthew 23:23-4].

Nor did Cameron bear in mind, when he exercised the summit veto the other week, another dictum of Christ’s quoted by Matthew: “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” [Matthew 19:19]. Nowhere do the gospels suggest that Christ advocated putting the British interest first. Funny, that.

This year's secular card manages to smuggle in very ostentatiously a touch of flag-waving

Of course, one can make a case for pretty much anything, however perverse or unchristian, with selected quotes from scripture. But these I have cited are widely-known and understood, even among those like me who find no place in their lives for supernatural mumbo-jumbo. It seems to me that those who publicly profess their conviction ought to act in a way that does not readily undermine the credibility of those convictions.

In sum, Britain is by no stretch of the imagination a Christian country. And nor does it labour under a Christian government. I wish all my readers a very cool Yule.

The Prime Minister has declared Britain “a Christian country … and we should not be afraid to say so”. It’s not unusual, of course, for politicians to make assertions that have no basis in fact. Sometimes this is done out of ignorance, sometimes out of dishonesty, sometimes out of self-denial, sometimes out of malice, sometimes out of hubris, sometimes out of simple foolishness. It’s hard to know which – if not all – of these is the wellspring of Cameron’s announcement. But, whichever way you cut it, it is not true.

In the most recently published results of the British Social Attitudes survey, those accounting themselves as Church of England were below twenty percent. Non-denominational Christians were under ten percent and Catholics less than nine percent. Those who said they had no religion of any kind numbered a little over fifty percent. In other words, Britain is not even half a Christian country. Indeed, considerably more people are certainly not Christian than voted for the parties comprising the coalition government. For whom does Cameron believe he is speaking?

Cameron's Christmas cards don't do religion: this was last year's, emphasising his parental orientation

Given that he must know – his advisors anyway must have pointed out – that his claim would likely alienate and repel rather more listeners than it would please (and besides, those pleased would be overwhelmingly dominated by those whose support is already assured), what did he think he was up to? Can he have been fending off in a subterranean way those filthy foreigners in the non-C-of-E European Union: Catholic France, Belgium, Spain, Italy, Poland and Ireland, Lutheran-Calvinist Germany? Could it have been a low piece of point-scoring against the Jewish Ed Miliband? Was it a crude attempt to identify himself with the spirit of Christmas? If this latter, he’d have done better by volunteering to switch on the lights in Oxford Street or accepting a cameo in the Christmas Day editions of either Downton Abbey or Absolutely Fabulous. The seasonal worship indulged by the vast majority of the British electorate is of those great gods, Retail and Telly.

The obvious question arising from Cameron’s asseveration is: does this supposedly Christian nation have a Christian government? Well, let’s just consider how far it measures up to the more obvious of Christ’s teachings and tenets. To begin at the beginning: “I say unto you, It is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle, than for a rich man to enter into the kingdom of God” [Matthew 19:24]. Two-thirds of the Cabinet are millionaires, several of them (including Cameron) multi-millionaires. So ministers – all of them, it’s fair to say, because even the non-millionaires are rich by most people’s standards – are booked for eternal damnation; which rather reduces their credentials as Christians, wouldn’t you say?

On the subject of damnation, Matthew has another pertinent passage for this government: “Then shall [God] say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels:/For I was an hungred [i.e. hungry], and ye gave me no meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink:/I was a stranger, and ye took me not in: naked, and ye clothed me not: sick, and in prison, and ye visited me not:/Then shall they also answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungred, or athirst, or a stranger,or naked, or sick, or in prison, and did not minister unto thee?/Then shall he answer them, saying, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye did it not to one of the least of these, ye did it not to me” [Matthew 25:41-5].

You notice how Christ does not suggest that we are all in it together or that helping the deprived is too expensive because of the “mess” that God inherited or that there needs to be a “stranger” quota, at least among those from outside the European Union. It is a given that the “least” must be “ministered” to. Neither does Christ suggest that the top rate of tax ought to be lowered. The government clearly does not subscribe to the philosophy as expressed here in Matthew’s account.

The government’s constant harping on eliminating the deficit puts it on the side of the Pharisees whom Christ excoriated: “Woe unto you, scribes and Pharisees, hypocrites! for ye pay tithe of mint and anise and cummin, and have omitted the weightier matters of the law, judgment, mercy, and faith: these ought ye to have done, and not to leave the other undone./Ye blind guides, which strain at a gnat, and swallow a camel” [Matthew 23:23-4].

Nor did Cameron bear in mind, when he exercised the summit veto the other week, another dictum of Christ’s quoted by Matthew: “Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself” [Matthew 19:19]. Nowhere do the gospels suggest that Christ advocated putting the British interest first. Funny, that.

This year's secular card manages to smuggle in very ostentatiously a touch of flag-waving

Of course, one can make a case for pretty much anything, however perverse or unchristian, with selected quotes from scripture. But these I have cited are widely-known and understood, even among those like me who find no place in their lives for supernatural mumbo-jumbo. It seems to me that those who publicly profess their conviction ought to act in a way that does not readily undermine the credibility of those convictions.

In sum, Britain is by no stretch of the imagination a Christian country. And nor does it labour under a Christian government. I wish all my readers a very cool Yule.

Sunday, December 11, 2011

POOR’s SHOW

Ever since the decline of European Socialism in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the ’90s, capitalism has considered itself king of the world and has behaved accordingly. In Britain especially, the triumph of capitalism has been celebrated by successive governments, whether Conservative or nominally Labour. Under the spell of the Chicago school of economic theory, Margaret Thatcher played a key role, greatly accelerating the switch from a manufacturing to a service economy begun by Harold Wilson and James Callaghan. This switch was in part motivated by a desire – yelled by Tories, whispered by Labour – to “smash” the unions that had, in the Westminster demonology, “held the country to ransom”.

This melancholy history reaches its latest chapter in the exercise of the veto by David Cameron at the European summit that was designed to save the euro, the Eurozone and indeed the national economies of the member states. Cameron’s sound-bite summary, parroted endlessly by ministers, is that he stepped out of line “to protect the national interest”. Even were that the whole story, it hardly presents Britain as a welcome player in a mutually beneficial alliance of nations, as communitaire.

But of course his stance does nothing to benefit you and me. Cameron’s only desire has been to protect the interests of the city, which is to say the interests of his party’s paymasters. The banks feared new regulation from Brussels. Cameron claims to intend to impose his own regulation but we will believe it when we see it – don’t hold your breath.

There is nothing in these quixotic dramatics that bodes any good for Britain’s dwindling manufacturing sector, or indeed for our export drive and hence our growth prospects. And as for realpolitik, it is a blunder of astonishing puerility. If the Eurozone does not quickly recover its equilibrium, Merkel and Sarkozy will persuasively blame Cameron. If the Eurozone climbs back onto its feet, no one will thank Cameron and it will occur to no one to reward Britain with increased trade. It’s a lose-lose result. As former President of the European Commission and Italian prime minister Romano Prodi put it, “Britain has gained freedom and lost power”.

The financial sector continues to bewitch politicians, not just in Britain but across the globe. In Durban, the climate change talks inevitably reached the conclusion that international short-termist capital wanted: ineffectual muddle. Despite menacing and even sometimes angry noises from governments, the money markets continue to enjoy a lack of supervision that must make the black economy green with envy.

Why is this? Is the path being made smooth by under-the-counter “considerations”? Or is the general run of ministers too finance-illiterate to know how far the speculators and their accountants and lawyers are taking them for patsies? Why is it that nothing uttered or threatened by banks and financial consultants is taken with a whole sackful of salt? Do politicians not understand that, of all the lobbyists and vested interests with which they deal day in and day out, the city is the most powerful and the most sophisticated, with deep enough pockets to set any hare running, however fantastical, and confidently to expect the desired outcome?

Consider the credit ratings agencies. The best-known, largest and most powerful is Standard & Poor’s, but there are others: last month, the US government tripled the number of such agencies that it recognises. S&P’s has been busy of late. In August, it set the markets on their ears by downgrading the United States from its triple-A rating, the topmost rung. A couple of weeks ago, it downgraded France’s rating. And on the eve of the Eurozone summit, it declared that it was considering the ratings of fifteen of the member countries of the eurozone. These credit ratings determine the cost of governmental borrowing. Downgrading a nation’s ratings heaps vast extra expense on that nation’s costs.

So who are these people at Standard & Poor’s? Why should anybody pay them heed? Well, S&P’s finds its origins in charting and invigilating the books of America’s railroads. For getting on for half a century, it has been part of the portfolio of the dynastic publishing conglomerate McGraw-Hill. It makes its home in Manhattan, a short hop from Wall Street.

It’s important to note that S&P’s is just down the road from the speculators. It is not based in St Patrick’s Cathedral. It is not the voice of god. Nor is it infallible, as Archbishop Dolan would doubtless decree if it were indeed emanating from the Archdiocese of New York. Commenting on the agency’s musing-aloud about the Eurozone, The Wall Street Journal (prop: Rupert Murdoch) noted: “Less than five months after it made its dramatic decision to downgrade the biggest economy in the world, S&P’s has again put itself in the hot seat”.

Despite the ratings agencies’ edicts being unveiled by the news media as if they were carved in stone, these pronouncements are not only the frequent subject of dispute but also sometimes agreed even by the agencies themselves to be mistaken. For instance, Standard & Poor’s conceded a $2trillion error in the calculation that led it to downgrade the US rating. That ain’t peanuts. Perhaps to save a little face, S&P’s cleaved to its downgrade in spite of the error. But it speedily reversed its downgrading of France after the Élysée angrily rebutted the basis for the decision.

A long-term agency decision has occasioned a damaging disenchantment with credit ratings across the world’s markets, especially those in Europe. This was the maintenance of Greece’s status as a good risk for several years before the habitual imprudence of successive Greek governments was finally recognised in 2009 when the country had already experienced several months of civil unrest. Greece’s most supportive agency was Moody’s, another of the so-called Big Three in the credit-rating market (the third is Fitch). Moody’s, be it noted, was being paid half a million dollars a year by the Greek government. How far does a fat cheque condition the fixing of a favourable rating, do you suppose?

I repeat that the ratings issued by the self-appointed agencies do not have the force of either moral law or statutory application. They only become powerful because powerful people pay them heed. I do wonder what exactly constitutes the appeal process against a rating that costs a nation many millions of dollars in increased charges on national debt. Could a government sue an agency for damaging its economy and its freedom to trade? Is it possible to gain reparation for agency findings that impacted the finances of enterprises and individuals? After all, the agencies played a leading and inglorious role in the collapse of the American subprime mortgage market that led to the US government taking over the two leading government-sponsored enterprises in the mortgage field, popularly known as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

The overarching problem with the world of financial services is that everything therein is driven by subjective readings of more or less subterranean manoeuvrings. We are routinely told that the markets are “nervous”, that capital is “in flight” from this or that enterprise, that traders “don’t like” this or that enactment of governmental policy. Those of us who live in a rather starker world of fixed prices and incomes, plying our various trades according to what we can get rather than what we would ask, are apt to lose patience every time the city is in the news. “Man up” we think, reluctantly using a phrase that the boy racers of the markets will perhaps understand.

Why is the security of national economies allowed to depend on the whims of consultants and speculators who anyway have their own axes to grind and who, for all we know, are delivering their verdicts with only the lining of their own pockets in mind? Regulation? We should elect a few governments who are ready to tear down the paper castles of the financial sectors and instead dedicate national economies to the welfare of the people. We should expect our representatives to reclaim what used to be called “the commanding heights of the economy”. Oh dear, I think I may be calling for a revival of Socialism.

Ever since the decline of European Socialism in the 1980s and the collapse of the Soviet Union in the ’90s, capitalism has considered itself king of the world and has behaved accordingly. In Britain especially, the triumph of capitalism has been celebrated by successive governments, whether Conservative or nominally Labour. Under the spell of the Chicago school of economic theory, Margaret Thatcher played a key role, greatly accelerating the switch from a manufacturing to a service economy begun by Harold Wilson and James Callaghan. This switch was in part motivated by a desire – yelled by Tories, whispered by Labour – to “smash” the unions that had, in the Westminster demonology, “held the country to ransom”.

This melancholy history reaches its latest chapter in the exercise of the veto by David Cameron at the European summit that was designed to save the euro, the Eurozone and indeed the national economies of the member states. Cameron’s sound-bite summary, parroted endlessly by ministers, is that he stepped out of line “to protect the national interest”. Even were that the whole story, it hardly presents Britain as a welcome player in a mutually beneficial alliance of nations, as communitaire.

But of course his stance does nothing to benefit you and me. Cameron’s only desire has been to protect the interests of the city, which is to say the interests of his party’s paymasters. The banks feared new regulation from Brussels. Cameron claims to intend to impose his own regulation but we will believe it when we see it – don’t hold your breath.

There is nothing in these quixotic dramatics that bodes any good for Britain’s dwindling manufacturing sector, or indeed for our export drive and hence our growth prospects. And as for realpolitik, it is a blunder of astonishing puerility. If the Eurozone does not quickly recover its equilibrium, Merkel and Sarkozy will persuasively blame Cameron. If the Eurozone climbs back onto its feet, no one will thank Cameron and it will occur to no one to reward Britain with increased trade. It’s a lose-lose result. As former President of the European Commission and Italian prime minister Romano Prodi put it, “Britain has gained freedom and lost power”.

The financial sector continues to bewitch politicians, not just in Britain but across the globe. In Durban, the climate change talks inevitably reached the conclusion that international short-termist capital wanted: ineffectual muddle. Despite menacing and even sometimes angry noises from governments, the money markets continue to enjoy a lack of supervision that must make the black economy green with envy.

Why is this? Is the path being made smooth by under-the-counter “considerations”? Or is the general run of ministers too finance-illiterate to know how far the speculators and their accountants and lawyers are taking them for patsies? Why is it that nothing uttered or threatened by banks and financial consultants is taken with a whole sackful of salt? Do politicians not understand that, of all the lobbyists and vested interests with which they deal day in and day out, the city is the most powerful and the most sophisticated, with deep enough pockets to set any hare running, however fantastical, and confidently to expect the desired outcome?

Consider the credit ratings agencies. The best-known, largest and most powerful is Standard & Poor’s, but there are others: last month, the US government tripled the number of such agencies that it recognises. S&P’s has been busy of late. In August, it set the markets on their ears by downgrading the United States from its triple-A rating, the topmost rung. A couple of weeks ago, it downgraded France’s rating. And on the eve of the Eurozone summit, it declared that it was considering the ratings of fifteen of the member countries of the eurozone. These credit ratings determine the cost of governmental borrowing. Downgrading a nation’s ratings heaps vast extra expense on that nation’s costs.

So who are these people at Standard & Poor’s? Why should anybody pay them heed? Well, S&P’s finds its origins in charting and invigilating the books of America’s railroads. For getting on for half a century, it has been part of the portfolio of the dynastic publishing conglomerate McGraw-Hill. It makes its home in Manhattan, a short hop from Wall Street.

It’s important to note that S&P’s is just down the road from the speculators. It is not based in St Patrick’s Cathedral. It is not the voice of god. Nor is it infallible, as Archbishop Dolan would doubtless decree if it were indeed emanating from the Archdiocese of New York. Commenting on the agency’s musing-aloud about the Eurozone, The Wall Street Journal (prop: Rupert Murdoch) noted: “Less than five months after it made its dramatic decision to downgrade the biggest economy in the world, S&P’s has again put itself in the hot seat”.

Despite the ratings agencies’ edicts being unveiled by the news media as if they were carved in stone, these pronouncements are not only the frequent subject of dispute but also sometimes agreed even by the agencies themselves to be mistaken. For instance, Standard & Poor’s conceded a $2trillion error in the calculation that led it to downgrade the US rating. That ain’t peanuts. Perhaps to save a little face, S&P’s cleaved to its downgrade in spite of the error. But it speedily reversed its downgrading of France after the Élysée angrily rebutted the basis for the decision.

A long-term agency decision has occasioned a damaging disenchantment with credit ratings across the world’s markets, especially those in Europe. This was the maintenance of Greece’s status as a good risk for several years before the habitual imprudence of successive Greek governments was finally recognised in 2009 when the country had already experienced several months of civil unrest. Greece’s most supportive agency was Moody’s, another of the so-called Big Three in the credit-rating market (the third is Fitch). Moody’s, be it noted, was being paid half a million dollars a year by the Greek government. How far does a fat cheque condition the fixing of a favourable rating, do you suppose?

I repeat that the ratings issued by the self-appointed agencies do not have the force of either moral law or statutory application. They only become powerful because powerful people pay them heed. I do wonder what exactly constitutes the appeal process against a rating that costs a nation many millions of dollars in increased charges on national debt. Could a government sue an agency for damaging its economy and its freedom to trade? Is it possible to gain reparation for agency findings that impacted the finances of enterprises and individuals? After all, the agencies played a leading and inglorious role in the collapse of the American subprime mortgage market that led to the US government taking over the two leading government-sponsored enterprises in the mortgage field, popularly known as Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae.

The overarching problem with the world of financial services is that everything therein is driven by subjective readings of more or less subterranean manoeuvrings. We are routinely told that the markets are “nervous”, that capital is “in flight” from this or that enterprise, that traders “don’t like” this or that enactment of governmental policy. Those of us who live in a rather starker world of fixed prices and incomes, plying our various trades according to what we can get rather than what we would ask, are apt to lose patience every time the city is in the news. “Man up” we think, reluctantly using a phrase that the boy racers of the markets will perhaps understand.

Why is the security of national economies allowed to depend on the whims of consultants and speculators who anyway have their own axes to grind and who, for all we know, are delivering their verdicts with only the lining of their own pockets in mind? Regulation? We should elect a few governments who are ready to tear down the paper castles of the financial sectors and instead dedicate national economies to the welfare of the people. We should expect our representatives to reclaim what used to be called “the commanding heights of the economy”. Oh dear, I think I may be calling for a revival of Socialism.

Saturday, December 03, 2011

TRANSCENDENTAL ARGUMENT

Through a mist of tears, I caught up with the conclusion of My Transsexual Summer, Channel 4’s four-part fly-on-the-wall series. Seven strangers, ranging in age from 22 to 52, were brought together for four weekend “retreats”. The only common factor between them was transitioning – three from female to male, the rest the reverse route. Their progress along these transitions varied greatly: from a few weeks to four years of “living as” the gender opposite to the given, from hormone treatment but with no plans for surgery to undergoing genital “correction” during the first programme.

That the seven individuals were necessarily self-absorbed was no hindrance to an immediate atmosphere of mutual support. Hugging and weeping soon became the lingua franca but that was no bar to laughter and the odd interesting undercurrent. Those of them – the youngest – who could not utter a subordinate clause without prefacing it with the syntactically redundant “like” or adding to it the rhetorical “d’you know what I mean?” may, having seen themselves on the box, attempt to eradicate this dreary verbal tic. For the viewer, it was a modest price to pay for their candour and courage.

Lewis

Putting hitherto obscure people under the media spotlight is as old as broadcasting. What has changed radically over the years is the way that obscurity is mediated. Half a century ago, producers took a disciplined, even puritanical approach to pointing microphones and cameras at people in the sanctity of their lives. Charles Parker’s wonderful and imperishably influential Radio Ballads tapped into a rich oral tradition and linked it to ordinary people’s experiences as expressed through their music – literally, folk music. Parker’s approach was pursued in television in various ways by Philip Donnellan, Denis Mitchell, Charlie Squires, Harold Williamson, Edward Mirzoeff, Paul Watson, Roger Graef and others.

These film-makers were also tapping into the traditions of documentary-making for the cinema in the Soviet Union and, in the west, by Robert Flaherty and the Grierson school. Although their methods could sometimes be suspect – staging, scripting and even faking scenes – the intention was to create the sense that the people momentarily in the spotlight were there on their own terms.

Sarah

Though there has been a surprising revival in documentary for the big screen – especially in the States where serious non-fiction seems still to be greatly encouraged by PBS and independent cinema companies – swathes of routine documentary-making for British television have descended to a bankrupt aesthetic. Commissioning editors seem to believe that the audience will accept nothing unless it is said or shown by a supposed celebrity, however self-evidently unqualified to pontificate on the subject (or indeed on anything else). The audience cannot be trusted to watch and appreciate a stranger; an introduction must be effected by someone both viewer and stranger have (theoretically) heard of, even though the viewer and the stranger usually have rather more basis for a rapport than either has with the intermediary.

Frequently, also, members of the public only earn their place on the screen alongside the “stars” by dint of their utter singularity. This is “freak show television”, epidemic across the channels. The more grotesque and humiliating the disability, the more unusual and distorting the condition, the better the commissioning editors like it.

Fox

And then there is the most unspeakable genre of all, the crassly misnamed “reality television”, whereat people both unknown and known (though not mixed) submit themselves to situations that are very far from real. Indeed, the programmes depend for their (apparent) appeal on the increasing inordinacy of both the situations and the behaviour of the participants: a diminishing prospect, they will surely discover,

The premise of My Transsexual Summer might have cast it into the “freak show” category or the fringes of “reality television”, but thankfully in practice it did not. Producer Helen Richards had contrived a mechanism that permitted sufficient freedom for the participants to learn a little about and from each other and to get comfortable with each other and with the camera. The retreat venue obviously allowed for ease of filming but did not impose its own characteristics. More importantly, the forward planning allowed for judicious moving of the production away from the communal set-up and into the individuals’ environments.

Fire-eating is one of Donna's accomplishments

This expansion added greatly to the reach of the series’ engagement with the participants. In the matter of any kind of search for identity among the young, the role of the parents is central and Richards was lucky or shrewd (or both) with her casting, which opened up a range of parental reactions and methods of dealing with their offspring’s dramatic developments. If the estranged father of Lewis suddenly found a warmth and sensitivity towards his son because the camera was on him, so much the better for the camera and for Lewis.

Those parents – and an adorable grandma – who gamely took part did themselves great credit. Others were eloquent in their absence, including the 20 year-old daughter of the 52 year-old former policeman-cum-lorry driver. Is changing sex more difficult, more testing, more traumatising – both for the transsexual and for those close to her or him – when the changer is middle-aged? Clearly the subject does not lend itself to too many generalities. It depends on the case.

Max

Even so, during the course of the series, I could not help wondering whether the transition from female to male is easier, more satisfactory, more … do I mean “natural”? … than from male to female. Among the seven we met, at least, the women became very convincing (if camp) boys, whereas the men tended to face the problem of seeming like, in the words of Sarah in Programme One, “bad drag”. Vocally, becoming female is especially taxing, whereas hormone treatment appears to lower the transitioning women’s voices considerably. And of course facial hair helps a lot.

A couple of the group spoke shrewdly about the crucial matter of moving convincingly, especially walking, and (by implication) the larger picture of demeanour, of presentation. Genital surgery clearly assists here, obliging the transgender person to walk accordingly. But both the programme and my own observations of drag entertainers and transvestite civilians convinces me that the unselfconsciously loose and informal body language of men is much easier for women to acquire than is the unselfconscious poise and subtlety of women, especially the glamorous women that men always seem to want to become.

Karen, Lewis, Max and Drew

Of the seven, the most “successful” transitioner appeared to be Donna: that is to say, the most confident and outgoing and – more important for transgender people even than for lesbian, gay and bisexual people (and, come to that, for straight people too) – the most comfortable in her own sexuality. Donna admits to having self-harmed in her teens but now, at 25, has been on hormones for two years and presents a persuasively female shape. Her breasts have developed but she knows how to present them too.

Still, she has no plans to seek surgery. For the females-to-males, chest surgery was/is part of the process and Lewis longs for a penis of his own, even if erecting it requires mechanical assistance. For her part, Donna gaily frequents bars where men go to meet transitional women who have not had surgery. She perhaps will settle for a hermaphroditic state. As a personality and a presence, the while, she appears – successfully and in many ways to her advantage – to carry off the trick of enjoying many of the advantages of both women and men.

Donna’s strongest suit is that she is not prepared to defer to anyone. She is sure of her place in the world and will fight to keep it. All the other transitioners recognised that and drew on it. We should too.

Through a mist of tears, I caught up with the conclusion of My Transsexual Summer, Channel 4’s four-part fly-on-the-wall series. Seven strangers, ranging in age from 22 to 52, were brought together for four weekend “retreats”. The only common factor between them was transitioning – three from female to male, the rest the reverse route. Their progress along these transitions varied greatly: from a few weeks to four years of “living as” the gender opposite to the given, from hormone treatment but with no plans for surgery to undergoing genital “correction” during the first programme.

That the seven individuals were necessarily self-absorbed was no hindrance to an immediate atmosphere of mutual support. Hugging and weeping soon became the lingua franca but that was no bar to laughter and the odd interesting undercurrent. Those of them – the youngest – who could not utter a subordinate clause without prefacing it with the syntactically redundant “like” or adding to it the rhetorical “d’you know what I mean?” may, having seen themselves on the box, attempt to eradicate this dreary verbal tic. For the viewer, it was a modest price to pay for their candour and courage.

Lewis

Putting hitherto obscure people under the media spotlight is as old as broadcasting. What has changed radically over the years is the way that obscurity is mediated. Half a century ago, producers took a disciplined, even puritanical approach to pointing microphones and cameras at people in the sanctity of their lives. Charles Parker’s wonderful and imperishably influential Radio Ballads tapped into a rich oral tradition and linked it to ordinary people’s experiences as expressed through their music – literally, folk music. Parker’s approach was pursued in television in various ways by Philip Donnellan, Denis Mitchell, Charlie Squires, Harold Williamson, Edward Mirzoeff, Paul Watson, Roger Graef and others.

These film-makers were also tapping into the traditions of documentary-making for the cinema in the Soviet Union and, in the west, by Robert Flaherty and the Grierson school. Although their methods could sometimes be suspect – staging, scripting and even faking scenes – the intention was to create the sense that the people momentarily in the spotlight were there on their own terms.

Sarah

Though there has been a surprising revival in documentary for the big screen – especially in the States where serious non-fiction seems still to be greatly encouraged by PBS and independent cinema companies – swathes of routine documentary-making for British television have descended to a bankrupt aesthetic. Commissioning editors seem to believe that the audience will accept nothing unless it is said or shown by a supposed celebrity, however self-evidently unqualified to pontificate on the subject (or indeed on anything else). The audience cannot be trusted to watch and appreciate a stranger; an introduction must be effected by someone both viewer and stranger have (theoretically) heard of, even though the viewer and the stranger usually have rather more basis for a rapport than either has with the intermediary.

Frequently, also, members of the public only earn their place on the screen alongside the “stars” by dint of their utter singularity. This is “freak show television”, epidemic across the channels. The more grotesque and humiliating the disability, the more unusual and distorting the condition, the better the commissioning editors like it.

Fox

And then there is the most unspeakable genre of all, the crassly misnamed “reality television”, whereat people both unknown and known (though not mixed) submit themselves to situations that are very far from real. Indeed, the programmes depend for their (apparent) appeal on the increasing inordinacy of both the situations and the behaviour of the participants: a diminishing prospect, they will surely discover,

The premise of My Transsexual Summer might have cast it into the “freak show” category or the fringes of “reality television”, but thankfully in practice it did not. Producer Helen Richards had contrived a mechanism that permitted sufficient freedom for the participants to learn a little about and from each other and to get comfortable with each other and with the camera. The retreat venue obviously allowed for ease of filming but did not impose its own characteristics. More importantly, the forward planning allowed for judicious moving of the production away from the communal set-up and into the individuals’ environments.

Fire-eating is one of Donna's accomplishments

This expansion added greatly to the reach of the series’ engagement with the participants. In the matter of any kind of search for identity among the young, the role of the parents is central and Richards was lucky or shrewd (or both) with her casting, which opened up a range of parental reactions and methods of dealing with their offspring’s dramatic developments. If the estranged father of Lewis suddenly found a warmth and sensitivity towards his son because the camera was on him, so much the better for the camera and for Lewis.

Those parents – and an adorable grandma – who gamely took part did themselves great credit. Others were eloquent in their absence, including the 20 year-old daughter of the 52 year-old former policeman-cum-lorry driver. Is changing sex more difficult, more testing, more traumatising – both for the transsexual and for those close to her or him – when the changer is middle-aged? Clearly the subject does not lend itself to too many generalities. It depends on the case.

Max

Even so, during the course of the series, I could not help wondering whether the transition from female to male is easier, more satisfactory, more … do I mean “natural”? … than from male to female. Among the seven we met, at least, the women became very convincing (if camp) boys, whereas the men tended to face the problem of seeming like, in the words of Sarah in Programme One, “bad drag”. Vocally, becoming female is especially taxing, whereas hormone treatment appears to lower the transitioning women’s voices considerably. And of course facial hair helps a lot.

A couple of the group spoke shrewdly about the crucial matter of moving convincingly, especially walking, and (by implication) the larger picture of demeanour, of presentation. Genital surgery clearly assists here, obliging the transgender person to walk accordingly. But both the programme and my own observations of drag entertainers and transvestite civilians convinces me that the unselfconsciously loose and informal body language of men is much easier for women to acquire than is the unselfconscious poise and subtlety of women, especially the glamorous women that men always seem to want to become.

Karen, Lewis, Max and Drew

Of the seven, the most “successful” transitioner appeared to be Donna: that is to say, the most confident and outgoing and – more important for transgender people even than for lesbian, gay and bisexual people (and, come to that, for straight people too) – the most comfortable in her own sexuality. Donna admits to having self-harmed in her teens but now, at 25, has been on hormones for two years and presents a persuasively female shape. Her breasts have developed but she knows how to present them too.

Still, she has no plans to seek surgery. For the females-to-males, chest surgery was/is part of the process and Lewis longs for a penis of his own, even if erecting it requires mechanical assistance. For her part, Donna gaily frequents bars where men go to meet transitional women who have not had surgery. She perhaps will settle for a hermaphroditic state. As a personality and a presence, the while, she appears – successfully and in many ways to her advantage – to carry off the trick of enjoying many of the advantages of both women and men.

Donna’s strongest suit is that she is not prepared to defer to anyone. She is sure of her place in the world and will fight to keep it. All the other transitioners recognised that and drew on it. We should too.

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

NEVER a SOFT or QUIET RUSSELL

For lively-minded people, the mid-teens are a dazzling voyage of discovery, a time when one starts seriously to explore identity, personality, friendship, sexuality, romance, psychology, politics, intellect, culture, self-expression and all the richness of existence and the world. Something that impacted forcibly on that period of my own life was the early work of Ken Russell.

Embraced and nurtured by the BBC at a time when the Corporation was fearlessly expanding and could train and encourage individual talent, Russell made a string of short documentaries of all kinds, including one on the young Salford playwright Shelagh Delaney (whose death preceded his own by only a few days), that was shown again on BBC4 just last year.

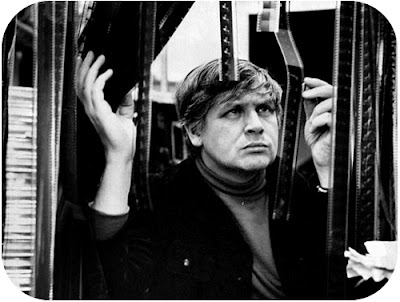

The young master considers his editing options

Then he was invited to join the Monitor team. This arts strand was the fiefdom of Huw Wheldon, a dynamic and deceptively avuncular Welshman with the public service ethic gushing through his veins. Wheldon was a fine editor, gathering about him programme-makers of exceptional ability and panache – John Boorman, John Berger, John Schlesinger, Humphrey Burton, Melvyn Bragg, David Jones – and he went on to be a canny managing director of television when the BBC led the world in innovative programming.

For Wheldon, Russell made a variety of programmes on a variety of arts and artists – Marie Rambert, Peter Blake, Le Douanier Rousseau – but it was his series of films about composers that marked him out and caught my own rapt attention. After more conventional portraits of Kurt Weill and Gordon Jacob, Russell persuaded the deeply dubious Wheldon to let him make a partly dramatised study of Edward Elgar. Wheldon would only agree to enactments without dialogue or identified actors. He, Wheldon, would speak the narration, which the two men wrote together.

Like all real artists, Russell rose gamely to the constraints. His film was elegiac but troubled, finding memorable images both to complement the music and to evoke the events of Elgar’s life and the struggles of his personality. The result was a triumph, kick-starting renewed interest in the music that has obtained ever since.

Sir (as he then wasn't) Huw Wheldon

And Wheldon, knowing a good thing when he saw it, accepted one composer portrait after another, each less constrained either in form or in content than the last. Prokofiev, Bartok and Debussy saw out Monitor’s run. By now, Russell had bankability for BBC managers and his ambitious and visually sumptuous portrait of the larger-than-life dancer Isadora Duncan was given a free-standing slot. It exercised the press for days and made a temporary star of the eccentric actress Vivian Pickles who took the lead. Karel Reisz later made a feature film of the same story starring Vanessa Redgrave but, though it offered Eastmancolor instead of the BBC’s black and white, the Russell is superior in every way, including cinematography (I’ll take Dick Bush and Brian Tufano in monochrome over Larry Pizer in colour any day).

Russell's image of the boy Elgar

After Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World, the offers of features came flooding in. Russell, who appreciated the autonomy granted by the BBC and knew well enough that cinema was much less flexible, played the studios off against the Corporation shrewdly over a few years. For the new BBC1 arts strand, Omnibus, he made five films. The penultimate was the finest thing he ever did. Song of Summer was a rapturous portrait of the blind and ailing composer Frederick Delius and his increasing dependence on the young composer Eric Fenby, for whom the word amanuensis seems practically to have been coined. Fenby was alive then – in 1968 – and he co-wrote the film with Russell.

Nowhere before or since did Russell so tenderly and instinctively tap into the mystery and agony of creation. The relationship delineated by Max Adrian as Delius and the former dancer Christopher Gable as Fenby is enthralling from beginning to end and much of the underpinning is provided by the radiant performance of Maureen Pryor as the devoted Jelka Delius. Just when you begin to get a sense that the filming may have fallen in love with its own rarefied atmosphere, Russell introduces a glorious passage of irreverent energy when David Collings as Percy Grainger invades the scene, racing up and down to throw and catch a cricket ball from either side of Delius’ house. Like everything in the piece, it is perfectly judged.

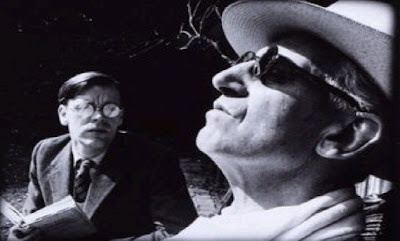

Oliver Reed in The Debussy Film

But Russell’s judgment was fitful. His next film was his most notorious: Dance of the Seven Veils, a riotous skit on the life of Richard Strauss and his supposed sympathy for the Nazi Party. It was so scattergun in its method and so inordinate in its traducing of Strauss’s reputation that there were questions in the House and the Strauss estate injuncted against it. I watched its transmission while coming down from an acid trip, in retrospect the ideal conditions. It seems unlikely that I will ever have the chance to see it straight.

By this time, Russell was an Oscar-nominated features director – for Women in Love – and, though his instincts about the lowering effect of the movie industry were on the button, he perhaps thought he could parlay a protected career. For a few years he did indeed get to make much of what he wanted, having started with a mix of idiosyncratic gossamer (French Dressing and a charming Lamorisse-inspired short called Amelia and the Angel) and hack work (Billion Dollar Brain).

Vivian Pickles (centre) as Isadora Duncan

Women in Love, a very confident and rather persuasive dramatisation (written by Larry The Normal Heart Kramer) of the Lawrence novel, gave Russell the clout to negotiate a continuation of his fantasy biographies of composers. He got to celebrate (and simultaneously mock) Tchaikovsky (The Music Lovers), Mahler and Liszt (Lisztomania) but clearly the audience for classical musicians was limited, especially as the movie-going demographic was growing ever younger. Nevertheless, for most of the 1970s, he managed to come across as a genuine auteur whose work could only be his – indeed, for a year or two, he, David Lean and Alfred Hitchcock were the only British directors whose names appeared above the title on posters.

It couldn’t last. The British movie industry was too fitful. Hollywood had firmly cast British directors as easily bullied but good with scripts and actors, and Russell fitted no part of that cliché. History was against him. With the exceptions of Boorman and Ken Loach, none of the directors who learned their trade in British television in the 1950s and ‘60s – Schlesinger, Philip Saville, Alan Bridges, Michael Apted, Alan Clarke, Claude Whatham, Michael Lindsay-Hogg, Alan Cooke, Roy Battersby, Mike Newell, Roland Joffé – got to make movies that were a patch on their television work.

Gable as Fenby, Adrian as Delius

Moreover, Russell was too wilful and irascible to look for ways to accommodate himself to front office and box office considerations. He couldn’t fashion a consistent and reliable methodology. Nor did he have the nous to show the executives a reassuring script. Russell’s screenplays were proverbially around forty pages long, a mere jumping-off point for what was in his head.

And he had no feel for the dynamics of performance. He veered between pliable people with whom he was familiar and stars handed to him. Though he worked with some fine players – Glenda Jackson often, Kathleen Turner, Alan Bates, William Hurt, Vanessa Redgrave, Natasha and Joely Richardson – he was more likely to cast limited or one-note actors – Oliver Reed often, Judith Paris often, Robert Powell, Richard Chamberlain, Ann-Margret, Vladek Sheybal, Theresa Russell (no relation), Andrew Faulds, Lindsay Kemp, Georgina Hale, Michael Gothard, Murray Melvin and – in the lead in Savage Messiah – Scott Antony who, to the evident disappointment of some, thereafter sank without trace. Another ineffectual regular was the away-with-the-fairies Hetty Baynes, at least during her period as Mrs Russell in the 1990s. I always imagined that her real name was Betty Haynes.

One of many striking compositions from Song of Summer

Russell also employed rather more than his share of non-actors to busk their way through: Roger Daltrey, Rudolf Nureyev, Twiggy, young Gable (to whose puppyish charms none could object), Christopher Logue, Michelle Phillips, Eleanor Fazan, Clive Goodwin, Caroline Coon, Ringo Starr, himself …

Russell clearly had a wonderful and instinctive rapport with music-makers, (though Sandy Wilson, who wept over the wild inflation of his modest pastiche of a musical, The Boy Friend, would not agree). He would have certainly subscribed to Walter Pater’s famous dictum that “all art aspires to the condition of music”. His own gift was for visualising. Much of his work is ravishing or at least eye-popping to look at. The source of this was his own immersion from an early age in cinema. Russell’s visual style harks back three generations, to that of Griffith, Eisenstein, DeMille and Von Stroheim. No director’s work resounds through his more than that of Fritz Lang, from whom Russell must have gained his penchant for symmetrical framing and expressionist camera angles.

Unlike the run of British directors, Russell was a born creator of film images. Most of those British reliables upon whom Hollywood leans are superb at reading scripts – other people’s scripts – and coaxing actors into bringing those scripts to life. But they are largely interchangeable, their work is not distinctive. Russell’s cinema is, for the most part, as unmistakeable as that of Michael Powell or Nicolas Roeg or Peter Greenaway or Mike Leigh or Danny Boyle or Christopher Nolan. And like most of them he often teetered on the tightrope. After Altered States, his hallucinogenic misfire of 1980, it became harder and harder for Russell to get his projects off the ground and although that has been true of every maverick movie-maker, including many greater than Russell – Powell, Orson Welles, von Stroheim, Stanley Kubrick. Roeg, Terry Gilliam – it is no less frustrating for someone full of notions.

The old monstre sacré

Mavericks tend to alienate critics and Russell was far from an exception. Indeed, so many commentators found his work vulgar, overblown, reckless with sources and shameless that a reputation as a monstre sacré became impossible to shake. Yet many serious and properly gifted people were happy to work with him, especially behind the scenes: Melvyn Bragg (who commissioned many of his last pieces for The South Bank Show), Peter Maxwell Davies, Derek Jarman, John Corigliano, Ferde Grofé, Douglas Slocombe, André Previn, Georges Delerue, David Watkin, Tony Walton …

Like many monomaniacs – and just about any movie director worth his salt is undoubtedly a monomaniac – Ken Russell was often his own worst enemy. He was certainly not the first, and he won’t be the last, whose pre-big-screen work is superior (often simply because less compromised) than his movies. And that applies to actors, writers and composers as well as to jobbing directors and auteurs like Russell. His BBC work certainly will pass the test of time, provided it remains available to see (some of it presently is not). And he added greatly to the excitement and stimulation of the age, not just for this highly receptive teenager.

For lively-minded people, the mid-teens are a dazzling voyage of discovery, a time when one starts seriously to explore identity, personality, friendship, sexuality, romance, psychology, politics, intellect, culture, self-expression and all the richness of existence and the world. Something that impacted forcibly on that period of my own life was the early work of Ken Russell.

Embraced and nurtured by the BBC at a time when the Corporation was fearlessly expanding and could train and encourage individual talent, Russell made a string of short documentaries of all kinds, including one on the young Salford playwright Shelagh Delaney (whose death preceded his own by only a few days), that was shown again on BBC4 just last year.

The young master considers his editing options

Then he was invited to join the Monitor team. This arts strand was the fiefdom of Huw Wheldon, a dynamic and deceptively avuncular Welshman with the public service ethic gushing through his veins. Wheldon was a fine editor, gathering about him programme-makers of exceptional ability and panache – John Boorman, John Berger, John Schlesinger, Humphrey Burton, Melvyn Bragg, David Jones – and he went on to be a canny managing director of television when the BBC led the world in innovative programming.

For Wheldon, Russell made a variety of programmes on a variety of arts and artists – Marie Rambert, Peter Blake, Le Douanier Rousseau – but it was his series of films about composers that marked him out and caught my own rapt attention. After more conventional portraits of Kurt Weill and Gordon Jacob, Russell persuaded the deeply dubious Wheldon to let him make a partly dramatised study of Edward Elgar. Wheldon would only agree to enactments without dialogue or identified actors. He, Wheldon, would speak the narration, which the two men wrote together.

Like all real artists, Russell rose gamely to the constraints. His film was elegiac but troubled, finding memorable images both to complement the music and to evoke the events of Elgar’s life and the struggles of his personality. The result was a triumph, kick-starting renewed interest in the music that has obtained ever since.

Sir (as he then wasn't) Huw Wheldon

And Wheldon, knowing a good thing when he saw it, accepted one composer portrait after another, each less constrained either in form or in content than the last. Prokofiev, Bartok and Debussy saw out Monitor’s run. By now, Russell had bankability for BBC managers and his ambitious and visually sumptuous portrait of the larger-than-life dancer Isadora Duncan was given a free-standing slot. It exercised the press for days and made a temporary star of the eccentric actress Vivian Pickles who took the lead. Karel Reisz later made a feature film of the same story starring Vanessa Redgrave but, though it offered Eastmancolor instead of the BBC’s black and white, the Russell is superior in every way, including cinematography (I’ll take Dick Bush and Brian Tufano in monochrome over Larry Pizer in colour any day).

Russell's image of the boy Elgar

After Isadora Duncan, the Biggest Dancer in the World, the offers of features came flooding in. Russell, who appreciated the autonomy granted by the BBC and knew well enough that cinema was much less flexible, played the studios off against the Corporation shrewdly over a few years. For the new BBC1 arts strand, Omnibus, he made five films. The penultimate was the finest thing he ever did. Song of Summer was a rapturous portrait of the blind and ailing composer Frederick Delius and his increasing dependence on the young composer Eric Fenby, for whom the word amanuensis seems practically to have been coined. Fenby was alive then – in 1968 – and he co-wrote the film with Russell.

Nowhere before or since did Russell so tenderly and instinctively tap into the mystery and agony of creation. The relationship delineated by Max Adrian as Delius and the former dancer Christopher Gable as Fenby is enthralling from beginning to end and much of the underpinning is provided by the radiant performance of Maureen Pryor as the devoted Jelka Delius. Just when you begin to get a sense that the filming may have fallen in love with its own rarefied atmosphere, Russell introduces a glorious passage of irreverent energy when David Collings as Percy Grainger invades the scene, racing up and down to throw and catch a cricket ball from either side of Delius’ house. Like everything in the piece, it is perfectly judged.

Oliver Reed in The Debussy Film

But Russell’s judgment was fitful. His next film was his most notorious: Dance of the Seven Veils, a riotous skit on the life of Richard Strauss and his supposed sympathy for the Nazi Party. It was so scattergun in its method and so inordinate in its traducing of Strauss’s reputation that there were questions in the House and the Strauss estate injuncted against it. I watched its transmission while coming down from an acid trip, in retrospect the ideal conditions. It seems unlikely that I will ever have the chance to see it straight.

By this time, Russell was an Oscar-nominated features director – for Women in Love – and, though his instincts about the lowering effect of the movie industry were on the button, he perhaps thought he could parlay a protected career. For a few years he did indeed get to make much of what he wanted, having started with a mix of idiosyncratic gossamer (French Dressing and a charming Lamorisse-inspired short called Amelia and the Angel) and hack work (Billion Dollar Brain).

Vivian Pickles (centre) as Isadora Duncan

Women in Love, a very confident and rather persuasive dramatisation (written by Larry The Normal Heart Kramer) of the Lawrence novel, gave Russell the clout to negotiate a continuation of his fantasy biographies of composers. He got to celebrate (and simultaneously mock) Tchaikovsky (The Music Lovers), Mahler and Liszt (Lisztomania) but clearly the audience for classical musicians was limited, especially as the movie-going demographic was growing ever younger. Nevertheless, for most of the 1970s, he managed to come across as a genuine auteur whose work could only be his – indeed, for a year or two, he, David Lean and Alfred Hitchcock were the only British directors whose names appeared above the title on posters.